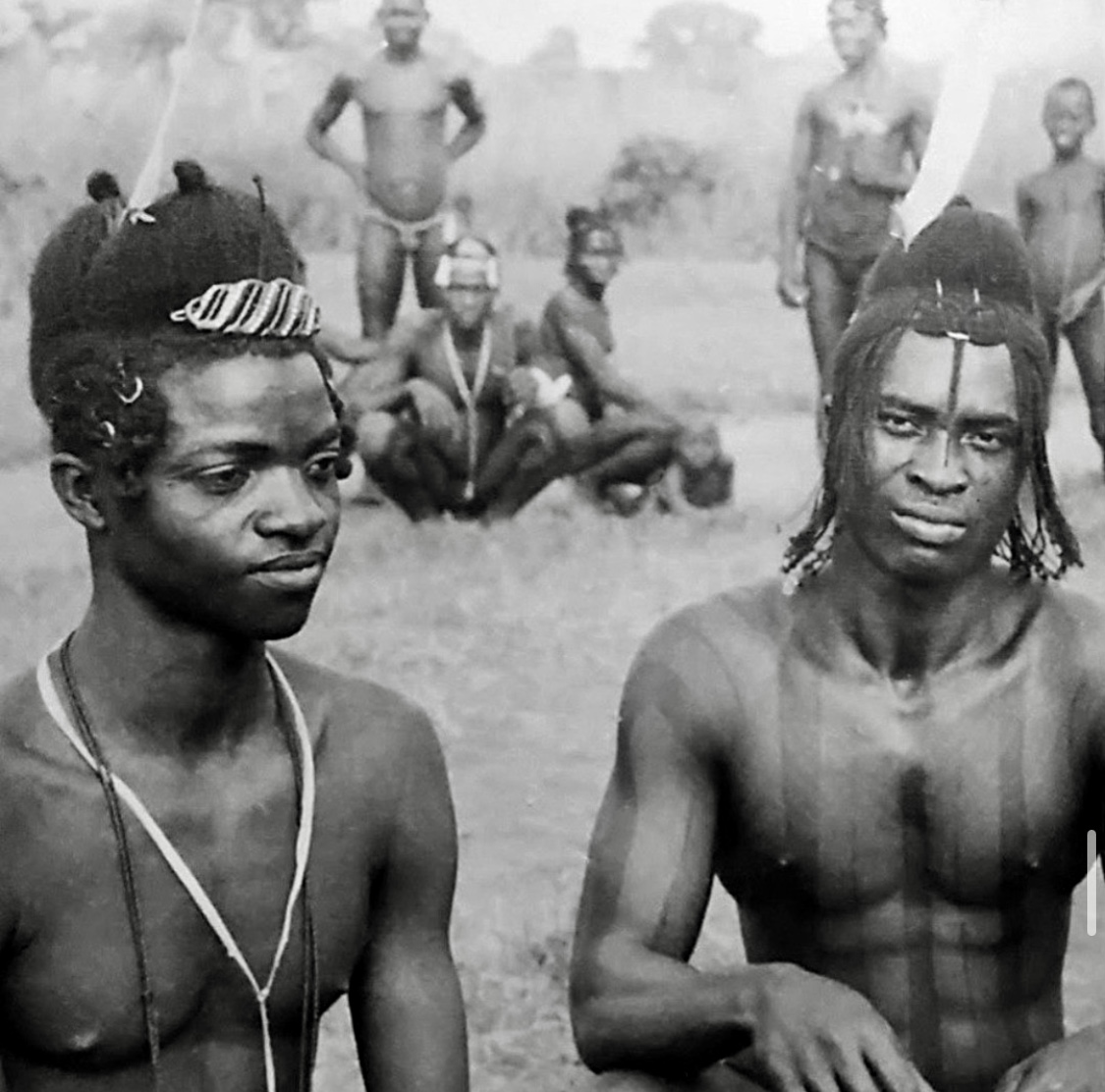

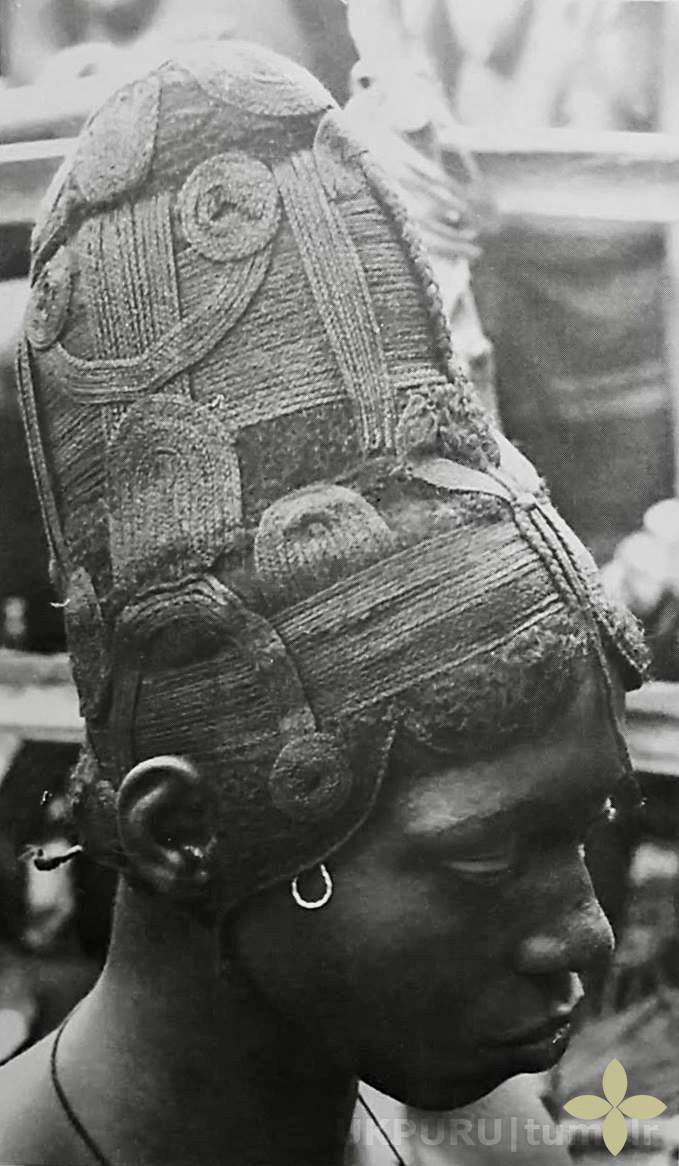

In 1939, British colonial art historian K. C. Murray photographed a group of young men belonging to the ogbolo age-grade in Achala, a community in the north-central Igbo area of Nigeria. This photograph, notable for its depiction of the young men adorned with uli body art and finely styled hair, captures a significant moment in Igbo cultural history. The image offers insights into the age-grade system, a critical social institution among the Igbo, as well as the artistic and aesthetic traditions associated with youth and masculinity.

The Ogbolo Age-Grade System

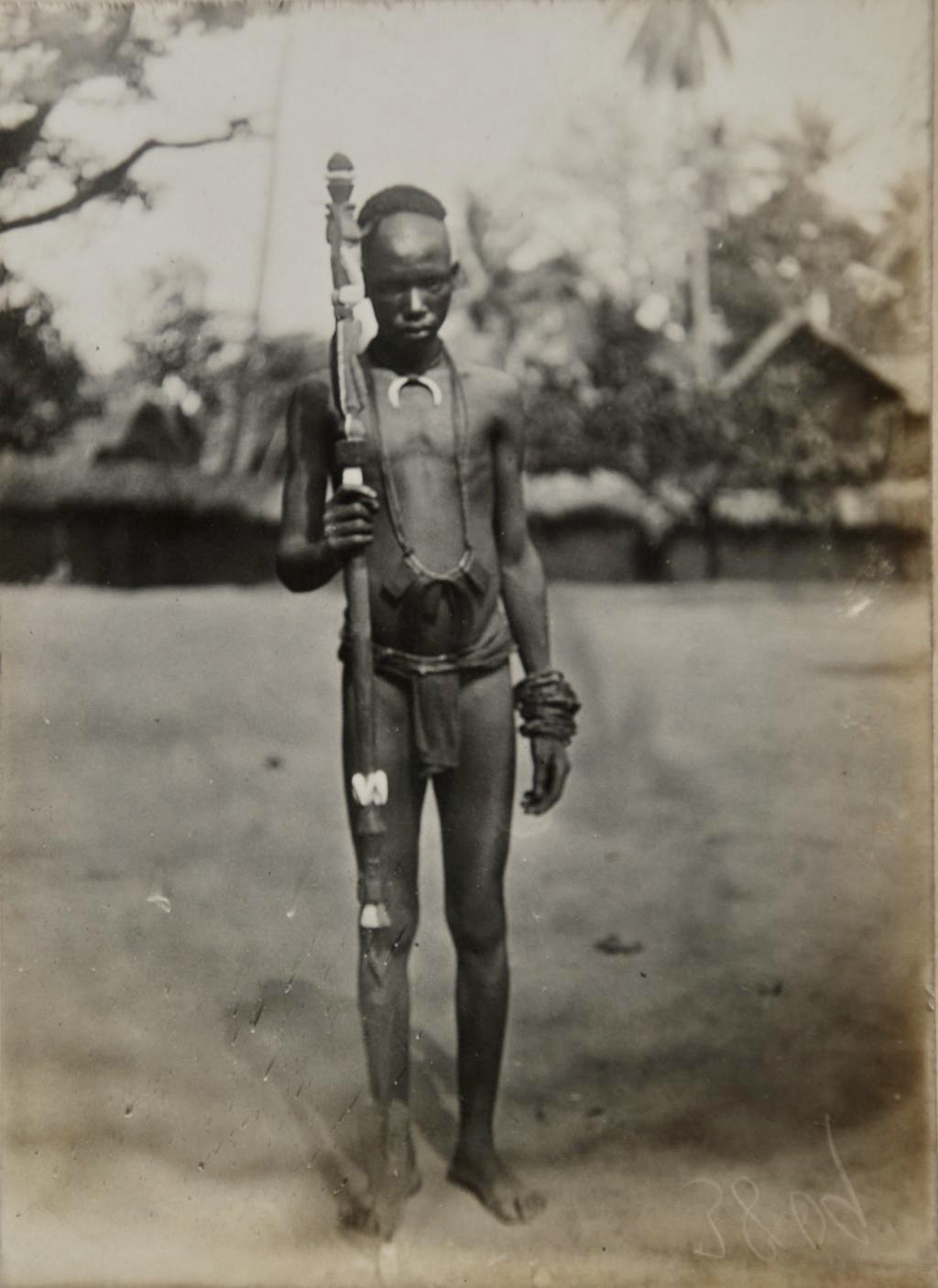

The ogbolo age-grade represents a distinct cohort of young men who, based on their approximate age and developmental stage, were grouped together for shared responsibilities and rites of passage. The age-grade system is a cornerstone of Igbo social organization, structuring communities into collaborative units responsible for various communal activities.

In Achala and other Igbo communities, young men of the ogbolo age-grade were tasked with roles such as:

•Participating in communal labor, such as road clearing and market building.

•Acting as defenders of the community during conflicts.

•Organizing and leading cultural festivals and ceremonies.

Membership in an age-grade also marked significant life transitions, such as the move from adolescence to adulthood. These rites of passage often involved elaborate celebrations, during which members of the age-grade would wear traditional adornments like uli and display intricate hairstyles to signify their readiness for adult responsibilities.

The Cultural Significance of Uli Body Art

Uli is a traditional Igbo body art form created using dyes extracted from the uli plant (Combretum paniculatum). Applied with a fine brush, uli designs consist of intricate geometric patterns and motifs inspired by nature and Igbo cosmology. These temporary tattoos were applied to the skin for special occasions, including age-grade ceremonies, festivals, and initiations.

For the young men of the ogbolo age-grade, uli served as a form of cultural expression, signifying their readiness to contribute to the community. The patterns were often symbolic, representing ideals such as strength, unity, and resilience. Women, who were traditionally the primary practitioners of uli art, used the designs to celebrate the youth’s passage into adulthood and their achievements.

Hairstyles as Markers of Identity

The hairstyles worn by the young men in Murray’s photograph are equally significant. Igbo hairstyles were traditionally elaborate, requiring skill and creativity to construct. For the ogbolo age-grade, these hairstyles symbolized status, individuality, and readiness for communal roles.

Common elements of these hairstyles included:

– Use of natural oils to give the hair a lustrous appearance.

– Shaving patterns or sculpting to create unique designs.

– Decorative elements such as beads, cowries, or dyes.

Hairstyles were not merely aesthetic but were often tied to cultural practices, signaling participation in ceremonies, social maturity, and communal pride.

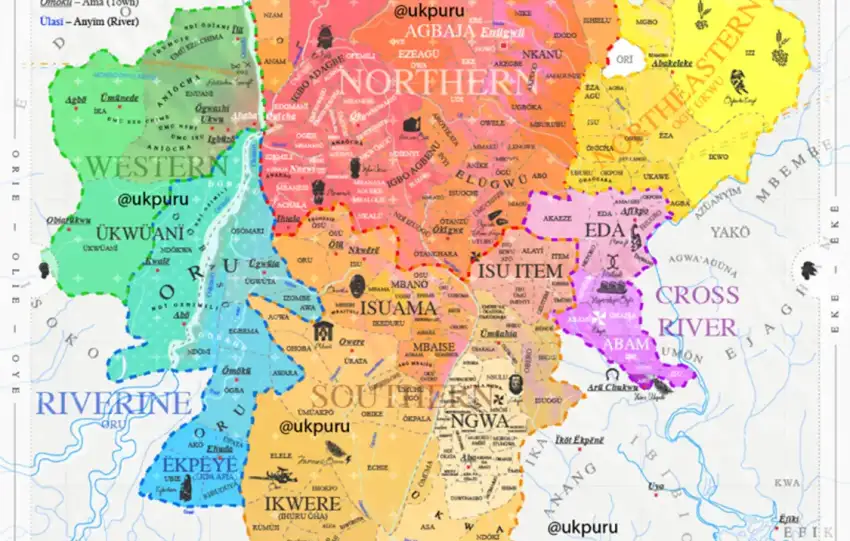

Achala and Its Cultural Context

Achala, located in the north-central Igbo region, is a community steeped in tradition. As part of the greater Igbo cultural area, it shares many practices with neighboring communities while also maintaining unique local variations. The ogbolo age-grade, uli designs, and hairstyles showcased in this photograph reflect the creativity and identity of Achala’s youth in 1939.

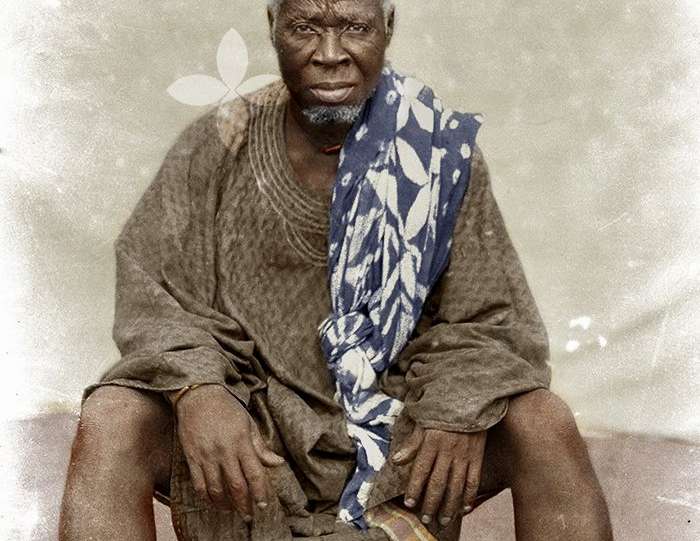

The Role of K. C. Murray in Documenting Igbo Culture

K. C. Murray served as an art historian and colonial administrator during a time when efforts were being made to document Nigerian art and culture. His photographs, including this image of the ogbolo age-grade, are valuable historical records of Igbo traditions.

However, Murray’s work, like much of colonial anthropology, must be critically evaluated for its limitations. While the photographs capture cultural practices with remarkable detail, they are often framed by colonial perspectives that may misrepresent or oversimplify African societies.

Preserving Igbo Heritage

Today, traditions such as uli and age-grade systems face challenges from modernization, urbanization, and the influence of global culture. However, efforts to preserve Igbo heritage have been gaining momentum. Artists, scholars, and cultural activists continue to celebrate and reinterpret uli art and traditional hairstyles through exhibitions, festivals, and academic research.

The legacy of the ogbolo age-grade, as depicted in Murray’s photograph, remains a testament to the resilience and creativity of Igbo cultural practices. By revisiting these historical records, contemporary audiences can draw inspiration and learn from the rich traditions of the past.

References

Afigbo, A. E. (1981). Ropes of Sand: Studies in Igbo History and Culture. Oxford University Press.

Cole, H. M., & Aniakor, C. C. (1984). Igbo Arts: Community and Cosmos. Museum of Cultural History, UCLA.

Murray, K. C. (1939). Photographs and Documentation of Nigerian Art and Culture. Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge.

Nwafor, O. (2018). Art and Identity in Igbo Society: Uli and Traditional Hairstyles. African Studies Review, 15(3), 135–162.

Okeke-Agulu, C. (2006). Art and Authority in Igbo Culture. African Studies Review, 49(3), 1–21.

Talbot, P. A. (1926). The Peoples of Southern Nigeria: Ethnological and Linguistic Sketches.