WHO ARE THE OTTAM/OTAM PEOPLE?

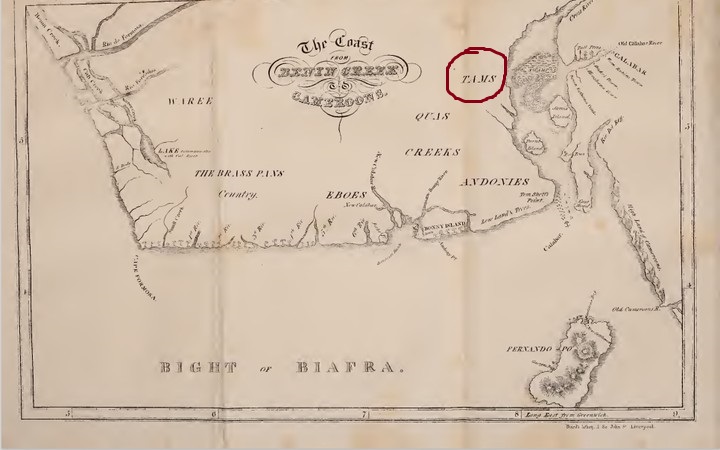

The Ndoki people, before the popularization of the Name Ndoki were known as “Otam/Ottam” people. This was recorded in Captain Crow’s Map and on the Dialect Mapping done by Rev. John Clarke in 1848 in Bonny

When Rev. John Clarke did a language Mapping in 1848 at Bonny, he mentioned an “Ottam” tribe located right in the same location where the Ndoki people are currently located. He also listed the wordlist of the Ottam people which accurately describes the Ndoki word list, especially the use of “Oli” for “One”

However what is not clear is whether the Ottam is a representation of the whole of the Ndoki people or a small section of the Ndoki people, but certainly, the Ottam people were part of the larger Ndoki tribe.

The Otam tribe was revered for their spiritual practices and ‘Mmoh’ worship and were distinguished by their robust physique, intricate body and facial markings.

This was captured by Captain High Crow of Liverpool, in his 1791 account where described them as follows:

‘The Ottam tribe are stout and robust and of a deeper black than any other tribes at Bonny. Their bodies and face are carved and tattooed in a frightful manner.’

The Otams were renowned for their spiritual practices, revering entities known as ‘Mmoh.’ In Bonny, they earned the name ‘Ottam Mmku’, reflecting their unique cultural identity.

In Crow’s account of the trade in Bonny, there was no mention of the word or name “Ndoki“, it was not popular at that time. Captain Crow (1789) recorded Ndoki as the “Ottam/Otam” tribe in Bonny. But in William Balfour Baike’s account (1859), 70 years later, it was mentioned 3 times, Signifying that the name had become more popular than the previous name which was Ottam/Otam.

The Ottam tribe’s remarkable physical strength, distinctive tribal marks, and bold nature earned them a popular name in Bonny, ‘Ottam Ahiriha.’ According to Ibani tradition

ORIGIN OF NWAOTAM MASQUERADE:

The Nwa-Ottam masquerade originated from a sacred, mystical grove in present-day Mkpajekere-Ndoki, formerly part of Ohambele-Ndoki. Initially, the Ndoki people, including the Ottam, worshipped ‘Mmoh’ (gods) believed to have heterosexual attributes.

It all started when a group of hunters stomped into a strange sight in the bush where some spirits were dancing. Among the strange group, one of them covered its face and was revered among the dancers. The hunters were revelled by the sight of what they saw as they watched the spirits dance and sway to the rhythm of the gods.

Upon their return, the hunters shared tales of their extraordinary encounter, inspiring the formation of a group to recreate the experience. This marked the inception of a revered cultural institution, now a cornerstone of Ndoki, Opobo, and Bonny traditions. The group established annual dance festivals, organized by age-grade systems known as ‘Ntuuma,’ to pay homage to these deities. Over time, the deity’s representation transformed into the iconic Nwaotam masquerade head, embodying the tribe’s rich cultural legacy.

From the name of the tribe, Ottam/Ottam, the name of the masquerade “Nwaotam” was derived, which can easily be translated to mean “product/child of Ottam/Otam”.

As the Ndoki deity’s ritual authority expanded, the Nwaotam masquerade’s core transformed into a robust cult, wielding significant spiritual influence and from Mpkajekere-Ndoki it began to spread down south via Opobo.

In 1920, a pivotal event occurred in Opobo’s cultural history when the Captain Uranta family, with King Arthur Mac Pepple’s blessings, transported the revered Nwa-Ottam head – a sacred male totem – from Mkpajekere to Queenstown, solidifying the Ntuma Mkpa tradition of the Nwaotam cult in their community. From Opobo it began to spread into neighbouring towns.it such as Bonny, Ikwerre, Ogoni, Andoni, Okrika, etc

According to tradition, the Ndoki people have maintained a long-standing affinity with the Ubani/Ibani people of Bonny and Opobo, rooted in a shared heritage. Historical records reveal that the founding fathers of Bonny originated from the Ndoki area, Opobo town is populated by the Bonny people. This shared history fostered enduring connections, which caused the Ubani/Ibani people to regularly travel upstream via the Imo River to Ndoki for trade, cultural exchange, and social interactions since Bonny’s inception. Due to this regular upward journey into Ndoki, they borrowed the Nwaotam Masquerade from the Ndoki people.

MYTH OF THE NWAOTAM MASQUERADE:

Initially, the Nwaotam cult operated as a secretive society with a rigid hierarchy, wielding significant religious and judicial influence, similar to its counterpart in the Cross River Region and hinterland area. However, over time, it struggled to maintain its original structure.

Eventually, the cult evolved into a vibrant carnival procession, showcasing its rich cultural heritage. Although its religious and judicial significance was diluted, the Nwaotam masquerade remains guided by the following enduring myths:

- The Tribal Mark Myth: According to tradition, the Nwaotam spirit (Mmoh), the ancestral deity of the Ottam people, is symbolized by the masquerade head’s distinctive features: prominent tribal marks resembling deep gashes, a strong and fierce facial expression, and an uplifted gaze signifying communication with the divine (‘Chineke’). These markings honour the original mummified totems and embody the spirit’s guiding presence.

- The Myth of Cemetery: The Nwaottam cult pays homage to ancestors and deceased town leaders. Members (Ntuma, Mkpa, Uke Mkpa) visit the cemetery seven days before the display, appeasing ancestral spirits (Ndi Itchie’ and seeking spiritual empowerment.

- The Myth of Spirit’s Gender: The ancestral spirits of Nwaotam are believed to possess dual male-female personalities. The original Queenstown’s totem was the male counterpart to Mkpajekere Ndoki’s primary masquerade. The female spirit is considered more powerful and is only displayed every 7 (seven) years underscoring its sacred significance.

- The Myth of Peculiar Food Stuff: Nwaotam cult members believe that during ancestral communion, they must avoid food cooked by women and self-prepare yam, corn, and plantain.

- The Myth of Canons and Guns: The Nwaotam masquerade, embodying ancestral spirits, performs on rooftops, bringing good fortune to the town. Without touching its heels to the ground, it leaps down, symbolizing divine protection and communication with other town deities. While at the rooftops guns are fired at it as it dances on the roof swinging from left to right. In the background, canons are also fired to give it reverence.

- Myth of the Cult: As a secretive cult, Nwaotam’s inner practices are concealed from outsiders. Only initiated members of Ntuma Mkpa, Mkpa Nwaottam, and Oruke Mkpa understand the intricate rituals and spiritual practices. Though hidden, these myths and symbols inform of the essence of Nwaotam, forging a strong bond among members.

Today, Nwaotam has metamorphosed into a yearly carnival in Ndoki, Opobo, Bonny, Okrika, Ikwerre (notably Elelenwo Town), Ogoni, Andoni, Aba, etc. and attracts tourists from all corners of the country.

In Opobo, colourful Uke groups were formed and organized to dance alongside the Nwaotam. Uke groups such as Ugele Mkpa, Ofor-Nu-Ogu, Ejesilem (I have arrived), Uwa-Wu- Nke-Onye, Iye-Eke are the most popular among all the other Uke groups that were formed in Opobo. These Uke groups add spice and variety to the Nwaotam Masquerade Play.

The Nwaotam Festival is held during the last quarter of the year, between December and January. Various towns that perform the Nwaotam festival have designated days for the play. In Opobo it is usually held between 24th – 25th of December annually. In Ndoki, it is held between December to January in various towns.

Reference:

Hugh, C. (1830). Memoirs, of the Late Captain Hugh Crow, of Liverpool: Comprising a Narrative of His Life, Together with Descriptive Sketches of the Western Coast of Africa. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, & Green.

Baikie, William Balfour (1856). Narrative of an exploring voyage up the rivers Kwo’ra and Bi’nue. John Murray