“The first Europeans to visit Arochukwu, in 1901, noted with some surprise — since it contradicted what they had been led to expect by their superiors — that the Aro trade in factory goods was no less than their trade in slaves, and that in fact Palm oil seems to be the main export. [W.J. Venour,

“The Aro Country in Southern Nigeria,” Geographical Journal, 1902] Even Sir Ralph Moor, the chief creator of the myth that the Aro were solely slave traders and brigands, was compelled to admit that “the individual profits of the slave traffic, owing to the heavy tolls exacted on the roads [trade routes in the Igbo area were often tolled by the communities they ran through], together with other market tolls, have not really been great.'” Robert D. Jackson (1975). The Twenty Years War. pp. 32-33.

This quote, from Robert D. Jackson’s The Twenty Years War (1975), highlights the complexity of Aro trade dynamics and counters the common narrative that the Aro people were solely involved in the slave trade. Early European accounts, particularly from W.J. Venour and Sir Ralph Moor, reveal that Arochukwu was also a hub for legitimate trade, notably in palm oil, a major export of the region.

The quote also emphasizes how the British colonial narrative often misrepresented African economic activities to justify their conquests. It demonstrates how the Aro, while involved in the slave trade, were not solely dependent on it and engaged in a broader spectrum of commerce, including the trade of factory goods and agricultural products like palm oil. The system of tolls imposed by local communities further suggests a sophisticated economic and political structure within the Igbo area.

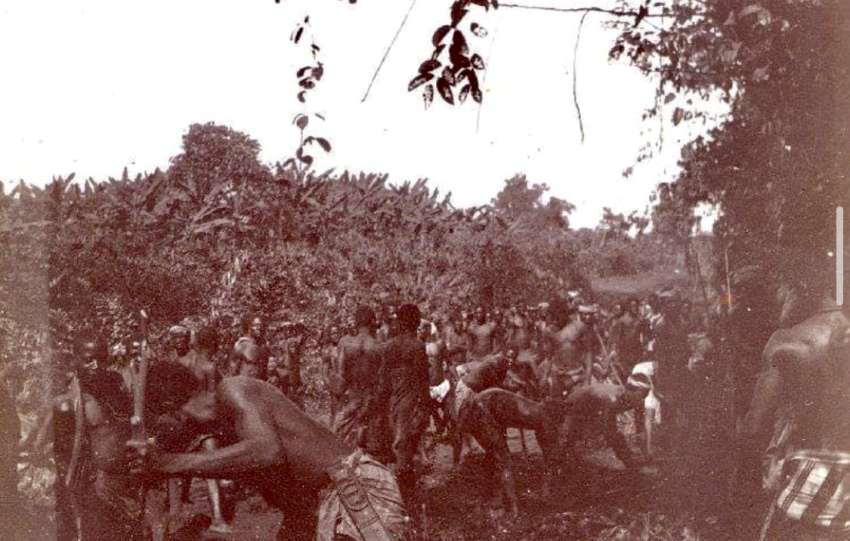

The photograph from Charles Partridge of a dance in Ibom, Arochukwu in 1903, adds a cultural layer, illustrating how life continued in the wake of British intervention.

It was not only economic ambitions that shaped the relations between the Aro Confederacy and European traders but also the need to respond to external threats/pressures. The expansion of European powers into Igbo territories made local kingdoms increasingly vulnerable. This encroachment introduced new demands, such as weaponry, which became vital in defense as this region rapidly destabilized. This raiding, largely to acquire European goods and arms, was accelerated by the Aro Confederacy against villages in the hinterlands of Igbo. In this way, captives from these raids were procured for the Atlantic slave trade, although that was not necessarily the main focus of Aro commerce.

In 1902, W.J. Venour recorded his observations in The Geographical Journal, where he provided a perspective different from that told in the prevailing stories. After his visit to Arochukwu, Venour recorded that trade in palm oil and factory goods was booming among the Aro people to a level equal to that of slaves. This was against the expectations of the British that Aro people were engaged only in slavery, thus underscoring the very active and multivalent economic network of the palm oil trade as a valuable product for their industries.

Sir Ralph Moor, the colonial official who was instrumental in establishing the myth of Aro dominance in slave trading, would later appreciate the fact that more profit was made from the tolls taken along trade routes than from the slave trade itself. He wrote, “The individual profits of the slave traffic…have not really been great,” identifying tolls along trade routes, not human trafficking, as the core of the Aro economy. This toll system underlined the Aro control over the trade routes, exposing a developed economic model that integrated several forms of commerce.

Historian Robert D. Jackson elaborates on these dynamics in his work, The Twenty Years War (1975), underlining the resourcefulness of the Aro. In particular, he indicated how, as European penetration became increasingly aggressive, the Aro shifted to palm oil and other “legitimate” exports and reduced their dependence on the slave trade. This would demonstrate that the Aro were pragmatic, carefully positioning themselves against the shifts within the world trade environment, while seeking self-determination within the colonial system, which at times distorted African commerce.

Further adding a cultural perspective to this history, a 1903 photograph by Charles Partridge depicted the Aro dance in Ibom, thereby illustrating Aro’s cultural life that was resilient in the face of disruptions to its trade networks brought on by British colonial forces. This photograph bears witness to the continued consistency in the tradition of the Aro and their commitment to cultural identity amidst outside pressures.

Reference:

- Jackson, R. D. (1975). The Twenty Years War. pp. 32-33.

- Venour, W. J. (1902). The Aro Country in Southern Nigeria. Geographical Journal.

- Partridge, C. (1903). [Photograph of a dance in Ibom, Arochukwu]

- Jackson, R. D. (1975). The Twenty Years War.

- Partridge, C. (1903). Photograph of Ibom dance.

- Venour, W. J. (1902). The Aro Country in Southern Nigeria. The Geographical Journal.

- Robins, J. E. (2021). From “Legitimate Commerce” to the “Scramble for Africa.” In Oil Palm: A Global History (pp. 42–74). North Carolina Scholarship Online.