Isuochi, located in Umunneochi Local Government Area of Abia State, Nigeria, is a significant community within the Igbo ethnic group. It is made up of several villages and towns. Towns in Isuochi include: Umuaku, Umuokpo, Umunnato, Umuohia, Amata, Oboro, Eziama, and Umuagba.

Known for its rich cultural heritage, vibrant traditions, and unique practices, Isuochi stands out as a beacon of Igbo identity. The community is deeply rooted in the larger Isu people, recognized as one of the largest Igbo subgroups. Historically, Isuochi has been a hub of cultural expression, social organization, and artistic creativity, with úrì body art serving as a distinctive hallmark of its cultural identity.

Origins of Isuochi

The Isuochi people trace their origins to the broader Isu subgroup, which occupies a central position in Igbo history. They are descendants of Ochi, a warrior and wrestler who settled in Nkwoagu from the Isuama area. The term “Isuama” refers to the south-central region of Igboland, often regarded as the heart of the Igbo nationality. Oral traditions suggest that the Isu people played a pivotal role in the development of Igbo culture, language, and socio-political organization. The Isuama area, including Isuochi, was historically significant for its role in trade and cultural exchange within Igboland.

The influence of the Nri Kingdom and the Aro Confederacy is evident in the social and cultural fabric of Isuochi. These powerful Igbo institutions shaped the religious, political, and artistic traditions of the community. Isuochi’s historical roots in these ancient systems underscore its importance as a cultural and historical site in Igbo heritage.

Cultural Practices of Isuochi

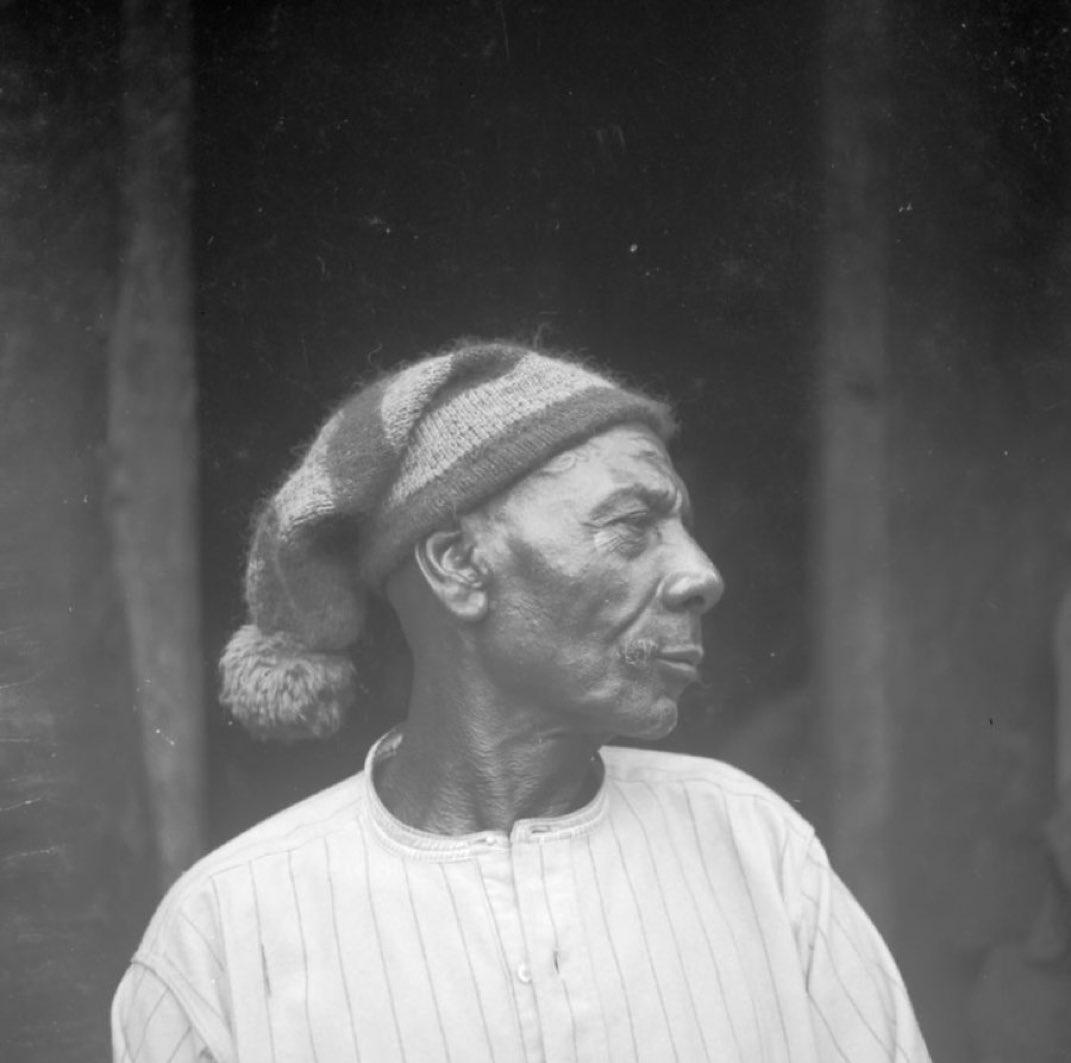

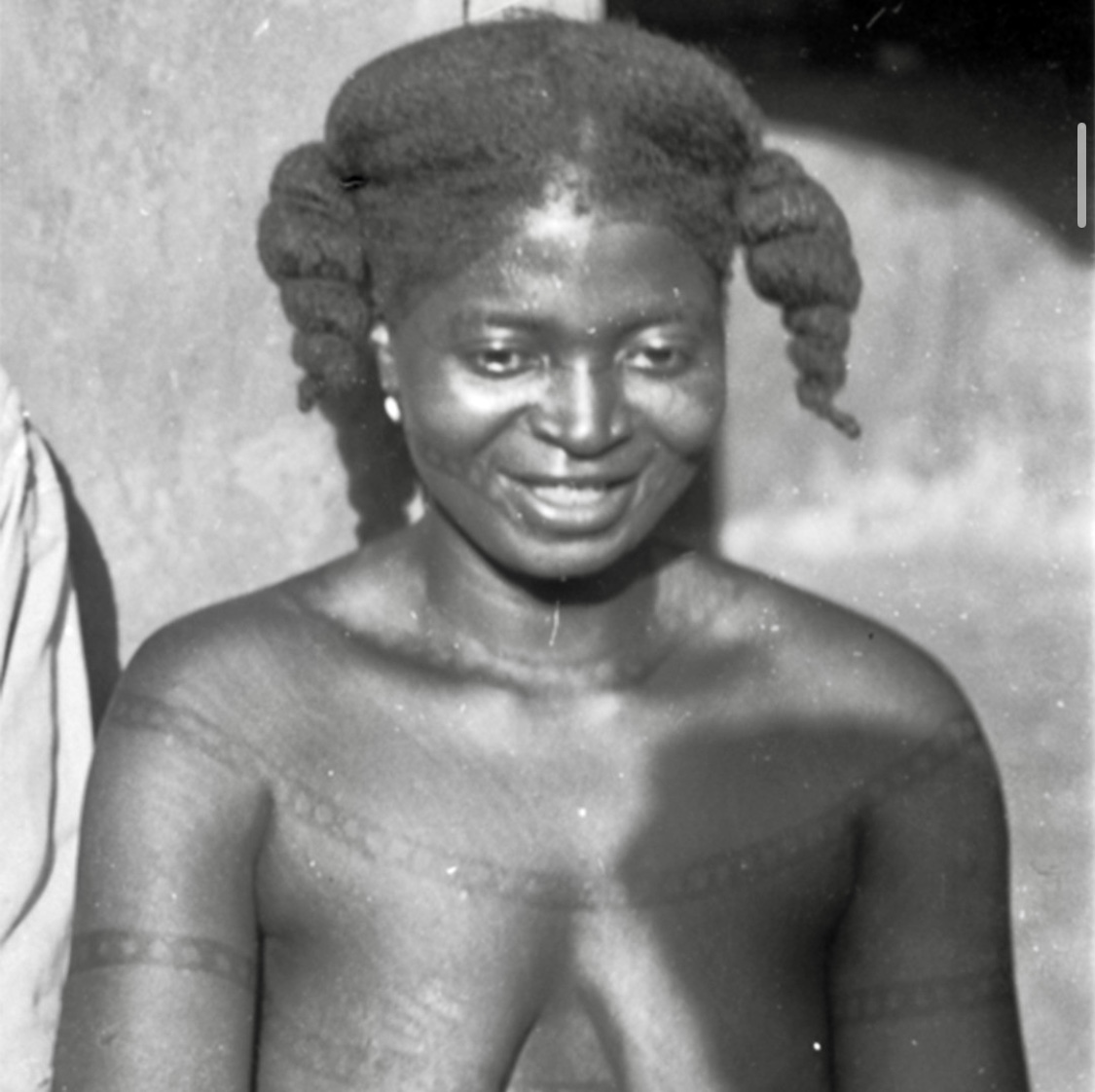

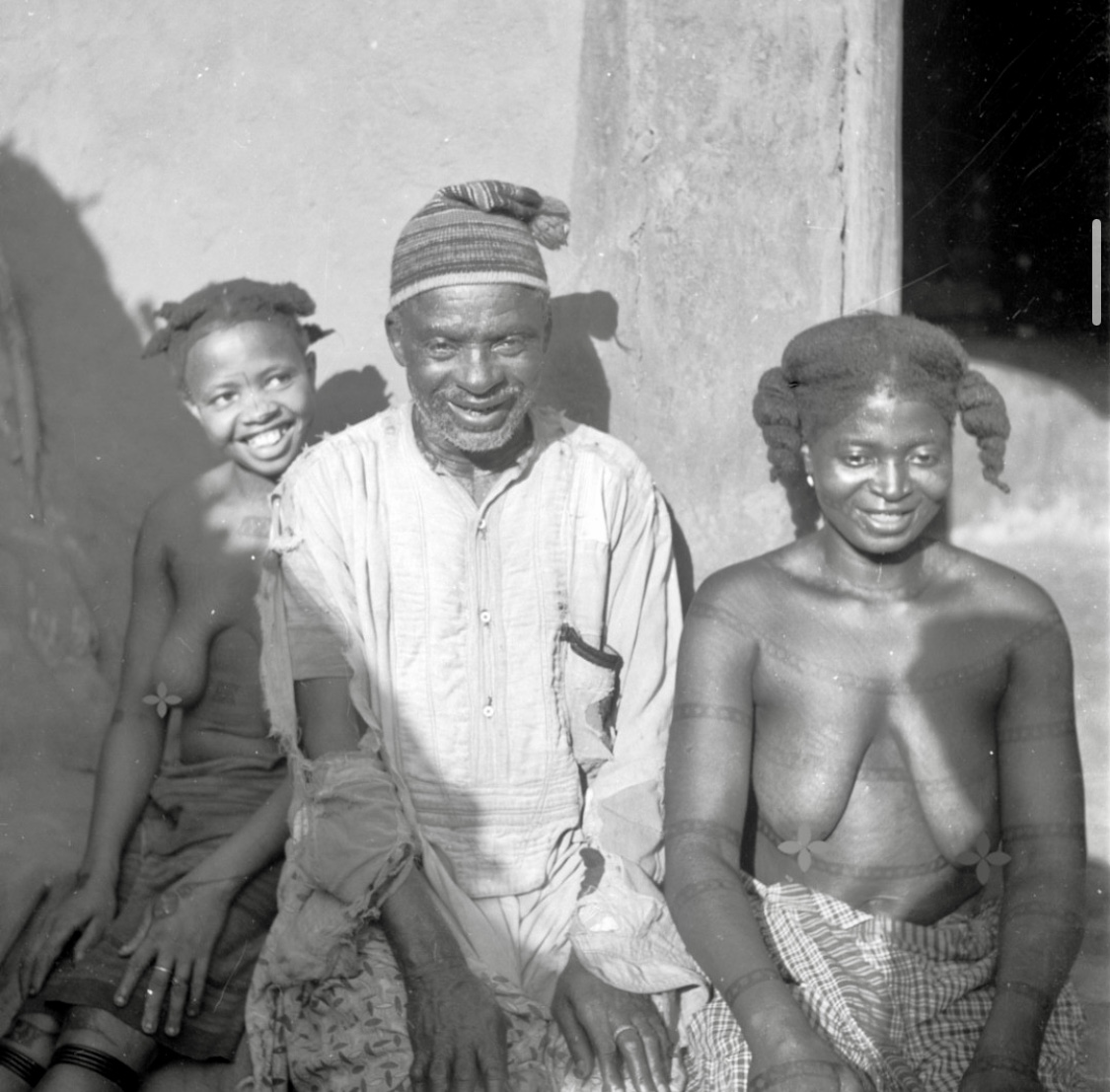

Isuochi is renowned for its dynamic cultural practices, including traditional arts, crafts, festivals, and rituals. One of the most notable artistic traditions is úrì, a form of body art that uses natural pigments to create intricate patterns on the skin. Documented by British anthropologist G.I. Jones in the 1930s, úrì holds aesthetic and symbolic significance. The patterns often communicate social status, rites of passage, and spiritual affiliations. The woman captured in Jones’s photograph adorned with úrì exemplifies the elegance and complexity of this cultural expression.

The ùrì body art of a lady who is from Isuochi (as the album was labelled) [cropped].

Photographed by G. I. Jones, 1930s.

Attractions in Isuochi

Ogbaukwu cave and waterfall are attractions in Umunneochi. Isuochi’s cultural festivals, traditional crafts, and historical significance make it a captivating destination for visitors interested in Igbo heritage. The New Yam Festival is particularly notable for its colorful displays, traditional attire, and communal feasting. Additionally, the visual documentation of úrì body art by G.I. Jones has elevated Isuochi’s cultural practices to international recognition, making it a subject of academic and artistic interest.

The preservation of Isuochi’s cultural identity is evident in its commitment to maintaining traditional practices while adapting to modern influences. Educational initiatives, media campaigns, and community projects have all contributed to the documentation and promotion of Isuochi’s unique heritage.

Conclusion

The cultural identity of Isuochi reflects a rich tapestry of history, artistry, and tradition. From its origins in the Isu subgroup to its vibrant festivals and the symbolic beauty of úrì body art, Isuochi stands as a testament to the resilience and creativity of the Igbo people. The community’s commitment to preserving its heritage ensures that its traditions remain a source of pride and inspiration for future generations.

References

Afigbo, A. E. (1981). Ropes of sand: Studies in Igbo history and culture. Ibadan: Oxford University Press.

Chukwu, O. A., & Anorue, L. I. (n.d.). Development communication: A social project in Isuochi and the role of the media. Department of Mass Communication, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria.

Isu people. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isu_people

Isuochi Home Town. (n.d.). In Facebook. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/Isuochihometown/

Jones, G. I. (1930s). Photographs of úrì body art and individuals from Isuochi. [Archival material]. Liverpool Museum, Liverpool, UK.

Liverpool Museum. (n.d.). Igbo body art and traditions: Archival collections. Retrieved from [insert link if available].

Njoku, O. N. (2001). Economic history of Nigeria: 19th and 20th centuries. Enugu: Magnet Business Enterprises.

Oriji, J. N. (1994). Traditions of Igbo origin: A study of pre-colonial population movements in Africa. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

The Isuochi Artisans: Implications of Traditional Arts and Crafts of Isuochi People. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijrth/v6-i1/1.pdf.