Many people in Akwa Ibom are unaware that an indigenous Igbo community exists in Ukanafun Local Government Area, called Ohaobu. This community’s name and its claim to hosting rights for a gas facility are strongly disputed by their neighbors.

When people think of ethnic groups in Akwa Ibom State, they usually think of the “Big Three”: Ibibio, Annang, and Oro. It took a long time before Ekid (from Eket and Esit Eket LGAs) and Obolo (from Eastern Obolo and Ibeno LGAs) were recognized as separate ethnic groups in the 1990s. Before this, they were considered part of the Ibibio.

However, few know that there are three other smaller indigenous ethnic groups in the state: Efik, Igbo, and Ogoni. These groups, known as the “Small Three,” have close relatives in neighboring Cross River, Abia, and Rivers States.

The Efik, who speak a language similar to Ibibio and Annang, are the largest of these smaller groups. There are three Efik-speaking clans in Akwa Ibom: two in Itu LGA and part of a clan in Okobo LGA. Itu is considered part of the Ibibio heartland, while Okobo is one of the Oro Nation’s five LGAs.

The Igbo and Ogoni communities are much smaller. Each group is concentrated in a single village—Igbo in Ukanafun and Ogoni in Oruk Anam. Both LGAs are largely dominated by the Annang people.

Geography of Akwa Ibom’s Igbo Community

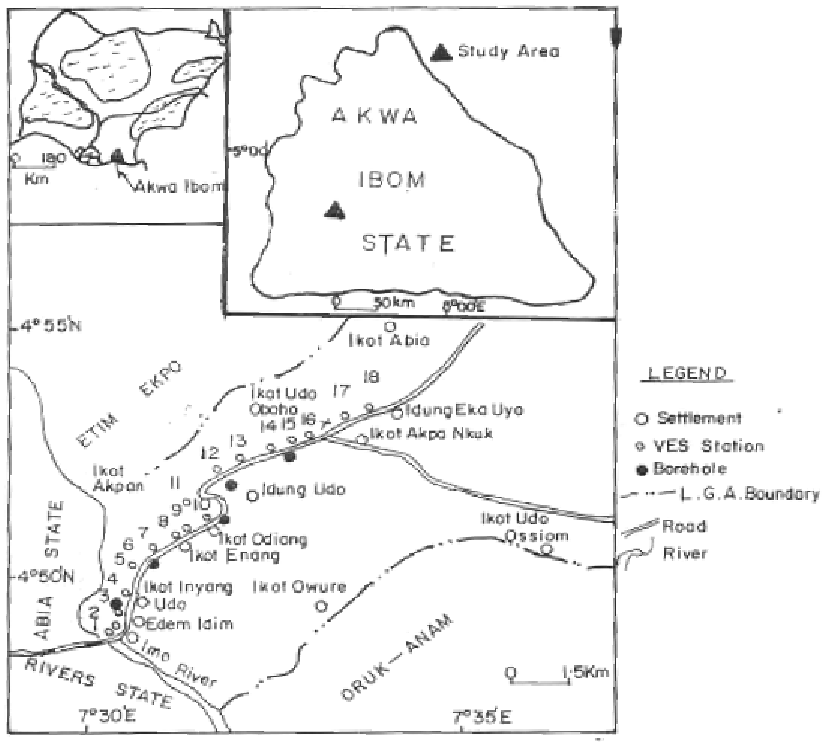

Ohaobu Ndoki, the name given by Akwa Ibom’s indigenous Igbo to their village, is in Southern Ukanafun Clan, specifically in Ward II. The village is about 7 kilometers from Ikot Akpa Nkuk, the headquarters of Ukanafun Local Government Area (LGA).

Ohaobu is surrounded by Ikot Inyang Udo to the east, Edem Idim to the south (both in the same ward), Ikpe Annang in Etim Ekpo LGA to the north, and the Blue River to the west. The river acts as a natural boundary, separating Ohaobu from Ukwa East LGA in Abia State and Oyigbo LGA in Rivers State, where their relatives live.

Although Ohaobu looks like a typical Akwa Ibom village with a rural setting, the widespread use of the Igbo language makes it stand out. Visitors often find it surprising that the village is part of Akwa Ibom.

Population

The Akwa Ibom State Government officially recognizes Ohaobu as Ikot Inyang Udo II. However, the villagers divide themselves into four smaller communities: Akpala, Okpikro, Umuchuta, and Ohaobu. With a population of over 2,000, they are part of the Ndoki, a subgroup of the Igbo ethnic group.

The Ndoki and their Asa relatives are prominent in Ukwa West and Ukwa East, the two oil-producing LGAs in Abia State, as well as Oyigbo LGA in Rivers State, home to the well-known Afam Power Station in Okoloma.

“We are the Ndoki of Akwa Ibom State,” says Pastor Magnus Kamanu, Secretary of Ohaobu Village Council. “The Ndoki are spread across three states, separated by the river.”

Occupation and Religion

Most of the people in Ohaobu work as farmers and fishermen. In the past, the Blue River, with its harbor in Ohaobu, was a hub for various activities, including smuggling goods from Cameroon to Aba and oil bunkering. These illegal activities were mostly carried out by outsiders, sometimes with help from locals. Because of this, the Federal Government set up a customs post near Ohaobu.

The majority of the villagers are Christians, mainly Anglicans. However, Christ Army Church and Assemblies of God Church also have many followers in the community.

How Ohaobu Became Part of Akwa Ibom

Ohaobu was originally part of the old Imo State, from which Abia State was created in 1991. In 1987, the Federal Government moved Ohaobu to Cross River State, which later became Akwa Ibom State. The river served as the natural boundary, based on the recommendation of a Boundary Adjustment Committee led by Alhaji Kaloma Ali, a lawyer and politician who later became Minister for Solid Minerals during General Sani Abacha’s regime.

The Dispute Over Ohaobu’s Name

There has been a long-standing disagreement about the village’s name. The Akwa Ibom State Government officially calls it Ikot Inyang Udo II, a name used by neighboring Annang communities in Ukanafun and Etim Ekpo LGAs. However, the people of Ohaobu reject this name, insisting on keeping their traditional name.

The village’s leader, Chief Lucky Nwosu, refused a recognition certificate from the Ministry of Local Government and Chieftaincy Affairs in 2023 because it had Ikot Inyang Udo II instead of Ohaobu. He explained, “We want the certificate in the name of Ohaobu. We are proud to be in Akwa Ibom but want our identity respected.”

The State Commissioner for Local Government and Chieftaincy Affairs, Udo Ekpenyong, has assured Chief Nwosu that the issue will be reviewed. Meanwhile, influential local politicians like Obong Eno Akpan, a former representative and commissioner, and Senator Chris Ekpenyong, have weighed in. While Ekpenyong supports Ohaobu’s demand, others, like the current representative of Ukanafun/Oruk Anam, Unyime Idem, believe adopting Ikot Inyang Udo II will better integrate the community into Akwa Ibom.

Arguments on Both Sides

The people of Ohaobu argue that their identity, culture, and history are tied to their name. Youth leader Simeon Nwaubani emphasized, “We have the right to our name, culture, and tradition. We were not handed over to Cross River State to lose our identity but for administrative reasons.”

However, state officials and some leaders believe the village should use the name in the official gazette. The Clan Head of Southern Ukanafun, Chief Friday Uko, stated, “The official name is Ikot Inyang Udo II. If they don’t want it, they can return to the other side of the river where their ancestors came from.” Despite this, he promised not to discriminate and assured Ohaobu of inclusion in the Clan Council once their Village Head is recognized.

The debate over Ohaobu’s name continues, reflecting deeper issues of identity and integration within Akwa Ibom.

When the Dispute Over a Name Turned Violent

On January 10, 2005, a State Government team came to Ohaobu to open the renovated Primary Health Centre. Everything was fine until the commissioner called it Primary Health Centre, Ikot Inyang Udo II instead of Ohaobu, as written on the wall. The crowd shouted in protest, and after the team left, chaos broke out. Angry youths accused the local ward councillor, Mr. Godwin Ekpe from Ikot Inyang Udo, of being behind the name change. To avoid being attacked, Ekpe had to be quickly escorted away. Looking back, Nwosu now says Ekpe wasn’t to blame.

Making Peace with Ikot Inyang Udo

Ohaobu and Ikot Inyang Udo have had a long-standing rivalry. People from Ikot Inyang Udo believe that Ohaobu settlers live on their land, which is why they prefer the name Ikot Inyang Udo II—the name recognized by the government.

The villages even went to court over the ownership of Ohaobu land and the village name. Tensions rose further when Ikot Inyang Udo supported Ikpe Annang in a land dispute with Ohaobu over where a Nigerian Gas Company (NGC) facility is located.

Today, things have changed. Ekpe, now a political leader in Ward II, says the two villages are united:

“We are one now. There’s no problem. We want peace and are no longer claiming the village. The government should recognize the name Ohaobu. My village agrees. You can’t force a name on anyone. I want peace in Ward II.”

A New Dispute: Who Owns the NGC Land?

Since 1996, Ohaobu and Ikpe Annang have argued over land where an NGC gas facility stands. The pipeline connects Alakiri in Rivers State to Ikot Abasi in Akwa Ibom, supplying gas to the Aluminium Smelter Company (ALSCON) and the Ibom Power Plant. Seven Energy also built another gas station there.

Ohaobu claims it owns the land. Youth leader Nwaubani says, “The facilities are in our community. The land belongs to Ohaobu.”

However, Engr. Akanimo Edet, a leader from Ikpe Annang, strongly disagrees:

“The NGC facility is in Ikpe Annang, not Ohaobu. This issue is settled.”

Despite their disagreements, Edet says the two villages don’t fight:

“We share a natural boundary and have family ties. The issue was just a boundary dispute when NGC arrived.”

When asked who NGC recognizes as the host community, Mrs. Willieba Albert from NGC’s Port Harcourt office declined to comment and referred questions to the company’s headquarters.

NGC’s Support to the Community

Ohaobu residents say they’ve received little from NGC. Nwaubani explains:

“We got compensation for trees and a water borehole, but it stopped working after three years. Seven Energy built a mini-town hall, and only a few locals got security jobs.”

In contrast, Edet says Ikpe Annang has benefitted more:

“We’ve received scholarships, jobs, water, road grading, and a well-equipped primary school.”

However, Edet believes NGC could do more and plans to reconnect with the company. Etim Ekpo’s Local Government Chairman, Mr. Udeme Eduo, confirms that past violence disrupted NGC’s community projects but is hopeful for renewed support:

“Etim Ekpo is safe now. Assistance should come through the Local Government to avoid conflicts over sharing.”

Meanwhile, Prof. Ime Udotong, NGC’s security consultant, has stayed silent on the issue. Despite being from Ikpe Annang, his family ties to Ohaobu suggest a complex relationship between the two communities.

Ohaobu’s Lack of Infrastructure

Ohaobu is missing basic infrastructure like good roads, electricity, and clean water. There’s no secondary school in the village, and the primary school has three broken-down classroom buildings.

“Our electricity project was launched by the State Government in 2009, but it only lasted a week,” says Nwosu. He’s asking the State Government to repair the seven-kilometer Anwa Uyo–Ohaobu Road that connects to the Local Government headquarters and wants the Federal Government to fix the Ohaobu–Azumini Road, which leads to Aba, a major commercial hub in Abia State.

Idiong, the Local Government Chairman, says he’s working on road repairs across Ukanafun and will get to Ohaobu soon. He explains that the previous delays were caused by violent cult activities in the area, but now that peace has returned, he’s focused on development. As a sign of progress, he points out that electricity has been restored at the Local Government Secretariat after seven years of blackout. His secretary, Elder Essien Akpanudo, also mentions plans to provide a borehole for clean water in Ohaobu.

Federal legislators Ekpenyong and Idem are also working on bringing development to the village through the Border Areas’ Development Agency. Ekpenyong recalls how, in 2001, he secured N30 million from Governor Victor Attah for projects like water supply, health center renovation, and school repairs in Ohaobu. Now, as a senator, he aims to bring projects to every ward in his district, including Ward II, to which Ohaobu belongs.

Idem plans to visit Ohaobu in March to hear from residents and better understand their needs: “I want to meet them directly, so I can help solve their problems,” he says.

Ido, another legislator, expresses deep concern: “The people of Ohaobu supported me. They need a lot of help. Their health center, electricity, and entire community need fixing. I’ve visited many times, and I’ll make sure they get the help they deserve.”

Broader Infrastructure Issues in Ward II

According to Ekpe, the leader of Ward II, Ohaobu’s problems reflect a larger issue affecting all nine villages in the ward. He points out that there’s only one secondary school for all nine villages, and most primary schools are in poor condition. “There’s no real development in Ward II,” he says.

Ekpe also calls on the State Government to build a bridge to Rivers State, where the government has already constructed a road to Obetie, the last village in Oyigbo LGA. He also wants the State to bring back the Special Development Area status that once covered Ohaobu and Ikot Inyang Udo. “Governor Attah declared us a Special Development Area, and he renovated our schools, but since then, nothing has happened,” he recalls.

He also mentions that Ward II has never had a Local Government Chairman or a House of Assembly Member, which he sees as political neglect.

In response, Idiong insists that Ward II is not being left out: “We’re sharing resources fairly. Ward II even has a Supervisor, while some wards have nothing.”

Blue River: An Untapped Tourism Treasure

Ohaobu is home to the famous Blue River, a natural wonder where the river runs parallel to the Imo River without mixing. This unique feature makes it a potential tourism hotspot.

Over a decade ago, Lady Valerie Ebe, then Commissioner for Culture and Tourism, visited Ohaobu to explore its tourism potential, but nothing happened afterward.

Akpanudo says the Local Government previously contacted the State Government about turning the river into a tourist attraction and is still waiting for action.

Nwosu urges the State Government to develop Ohaobu as a tourist destination. Ido promises to look into the matter and see what can be done.

Ohaobu’s Connection to Pro-Abia Groups in Ika and Etim Ekpo

Nwoko, the state’s top legal officer, compares Ohaobu in Ukanafun to Ikot Udo in Ika. He says Ohaobu’s situation is better because most people there agree they are part of Akwa Ibom, while in Ikot Udo, even brothers in the same family argue about being in Akwa Ibom or Abia.

“I know their story well,” Nwoko says. “Ohaobu people never claimed to be from Abia. They say they are from Akwa Ibom. The problem is just the name. In Ikot Udo, it’s worse. Some people say it’s part of Abia and call it Akarika Obu. Even within families, some say they are from Akwa Ibom, others from Abia. This isn’t a boundary issue with Abia but our own people claiming to be from Abia.”

Nwoko adds that similar disputes happen in Ini, Itu, and Ibiono Ibom LGAs, and the National Boundary Commission (NBC) is almost done tracing the boundaries. The National Assembly will pass a law to settle these disputes.

Eduo mentions that in Etim Ekpo, villages like Ikot Ama and Ikot Aja are divided too. “Some claim Abia, but most say Akwa Ibom,” he says. He also notes that one of those claiming Abia has even served as a Councillor in Abia.

Edet is firm: “The pro-Abia group is a minority. Most people say they are from Akwa Ibom, though a few claim Abia for benefits.”

First Igbo Councillor in Akwa Ibom

Nwosu, while loyal to Akwa Ibom, reminisces about their better days in old Imo State. He recalls that their leader, Onuoha, chaired the Imo State Council of Traditional Rulers and was awarded the Member of the Order of the Niger (MON). Now, Nwosu believes they are sidelined in Akwa Ibom, with no job or political opportunities.

Nwaubani is more vocal: “Ohaobu is not fully included in Akwa Ibom’s state or local government jobs or politics. We are happy in Akwa Ibom, but we need full integration.”

Akpanudo explains that this exclusion was because Ohaobu once distanced itself from Ukanafun. “They didn’t want to mix with Ukanafun people, so they missed out. Now, they’ve embraced us, and we see them as brothers.”

Change seems near. Assemblywoman Ido hints: “In the upcoming local election, we have good plans to ensure Ohaobu feels included. You’ll see it happen.”

Ekpe reveals the plan: Ohaobu will get the councillorship seat for Ward II in the 2020 local election, making it the first time an Igbo person will hold the position in Akwa Ibom.

Nwosu, who previously lost the councillorship bid, is thankful. “I appreciate Ekpe for supporting us. If he backs this, it will happen. We’re grateful to the ward leaders for zoning the position to us.”

Idiong supports Ohaobu’s turn: “If it’s their turn, why not? We rotate positions in Ukanafun.” He shares how Ohaobu even honored him for his peace efforts during tough times of militancy.

Akwa Ibom’s Indigenous Igbo Community

This shows Akwa Ibom has an indigenous Igbo population, not just Igbo settlers from other states. When listing ethnic groups in Akwa Ibom, it shouldn’t stop at five (Ibibio, Annang, Oro, Ekid, and Obolo). Igbo, Ogoni, and Efik should be included, proving Akwa Ibom is truly multi-ethnic.

There are many Igbo communities in present-day Akwa Ibom State. The Igbos living in these communities speak both Igbo and Ibibio fluently. These communities include:

- Ohaobu Ndoki Community in Ukanafun LGA of Akwa Ibom.

- Obuagu (meaning “Heart of a Lion”), another Igbo community, currently in Ini LGA.

There are also smaller communities located at the edges of Akwa Ibom, near the borders with Abia and Ebonyi States. These communities are mostly bilingual, speaking both Igbo and Annang fluently, and they often intermarry.

Such communities include the Itumbauzo communities in Ini LGA, Umubueze Village in Ika LGA, and other lesser-known communities in Ini, Obot Akara, Essien Udim, Ika, and Etim Ekpo LGAs of Akwa Ibom State.

References

- Aba, S. I. (2024). The ethnic dynamics of Akwa Ibom State: History and identity. Akwa Ibom Historical Society Press.

- Ekpenyong, U. A. (2023). The controversial name of Ohaobu: A cultural perspective. Journal of Nigerian Ethnic Studies, 15(3), 234–248.

- Kamanu, M. (2024, February 15). Personal interview on the history of Ohaobu and its boundary disputes.

- Nwaubani, S. (2023). Ohaobu’s struggle for recognition: A case study in identity and governance. Ukanafun Research Bulletin, 10(2), 45–60.

- Nigerian Gas Company. (2024). Corporate social responsibility report. Nigerian Gas Company.

- Ukanafun Local Government Council. (2023). Infrastructure development report. Ukanafun Local Government Council.