In the thick forests and open markets of Igboland, life was defined by vigilance. The booming sound of the Ikoro drum was not just music; it was an alarm of danger, a call to unity, and sometimes, the last sound villagers heard before attackers descended. From the Abam warriors to the Aro slave networks, Igboland became a battleground of survival. Yet amid fear, the Igbo also showed resilience through resistance, war strategies, and collective heroism.

“Otu onye anaghị agba mgba” (One person alone does not wrestle). This proverb captures the spirit of collective defense in Igboland during the centuries of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. No single person, family, or village could survive the onslaught of raids and kidnappings. It took alliances, strategies, and shared sacrifice to resist.

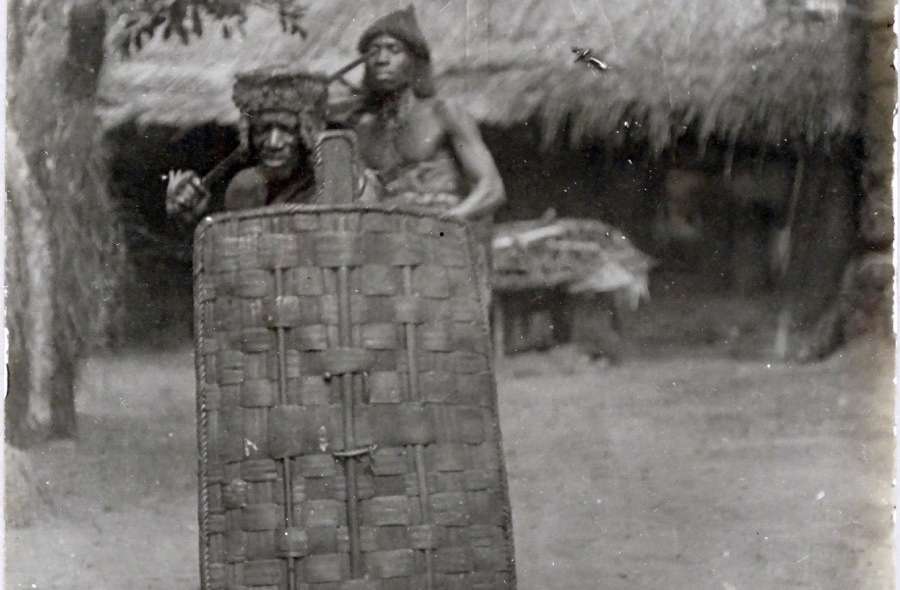

The Aro and Abam Networks

Central to the slave trade in Igboland were the Aro traders and their military allies, the Abam warriors. Armed and organized, the Abam raided villages, capturing men, women, and children, who were then funneled through Aro trade routes to coastal ports. Oral accounts describe the terror of their approach; flaming torches, sharpened machetes, and the ominous sound of war drums.

Yet the Igbo were never merely victims. Communities like Nri, Awka, and Enugu-Ukwu developed reputations for resistance, defiance, and spiritual protection. Nri, in particular, claimed authority from sacred traditions, refusing to shed blood but exercising influence through ritual sanctions against slave raiders.

Case Studies of Igbo Resistance

- The Vigilante Groups of Umuchu

Oral traditions recall how Umuchu formed bands of armed youths who ambushed raiders at night. Using poisoned arrows and hidden traps, they made their forests dangerous to outsiders. - Enugu-Ukwu and the Poisoned Food Strategy

In some towns, families would poison yam barns or water supplies, preferring death to capture. The chilling proverb illustrates this spirit: “Ka mmadụ nwụọ ka e were ya bụrụ ohu” (Better for one to die than to be enslaved). - Awka Ironworkers

Known for their skill in iron smelting, Awka men forged weapons to defend their settlements. Their forges, once symbols of industry, became centers of resistance.

The Ikoro Drum: Alarm and Unity

The Ikoro drum was more than an instrument; it was a voice of survival. Placed in village squares, it was beaten during emergencies to summon men to arms. Each community had unique rhythms, one for meetings, another for war. When the deep boom of the Ikoro echoed through the hills, everyone knew whether to gather or to flee.

A proverb reminds us: “Ọkpọkpụ anaghị akpọ ọkpọkpụ na-enweghị ihe mere” (A drum does not sound without cause). For Igbo communities, the drum was as vital as any sword or spear.

Heroic Figures and Stories

- Igbere (Igbo Erughi) — nicknamed “the town the Aro could not capture.” Oral memory celebrates how its warriors repelled attack after attack.

- Ngwa Militarization — In Southern Igboland, the Ngwa consecrated war deities and built powerful age-grade systems that trained young men for battle.

- Ese-Ịke and Oral Songs — War chants like Ese-Ịke were sung to inspire fighters. These songs, remembered in fragments today, gave rhythm to resistance and turned fear into courage.

Social Impact of Resistance

Resistance reshaped communities:

- Villages built fortified walls and moats.

- Marriage networks shifted, as families sought alliances with strong communities.

- Migration increased, with fugitive groups founding new settlements deep in forests or hills.

Still, the shadow of the slave trade lingered. Some villages prospered by collaborating with the Aro, while others suffered repeated losses. The complexity of Igbo resistance lies in this duality: survival sometimes meant compromise, while honor demanded defiance.

Legacy of War and Resistance

The stories of these struggles live on in Igbo memory. Place names, songs, and festivals still recall the days of vigilance. For instance, towns that resisted raids proudly retell their heroism during annual festivals. Families preserve names like Ọzọmgbachi (“one who resisted in war”) or Nwanyịdịm̀màgbọ (“a woman is also capable of war”), keeping the legacy alive.

“A gaghị ama mmadụ ihe ọma o mere ruo mgbe ọ nwụrụ” (A person’s good deeds are not fully known until after death). Today, remembering these stories honors those who defended Igboland from total devastation.

The Igbo response to slavery was not silence or surrender. Through strategies of resistance, collective defense, and cultural resilience, they turned survival into heroism. The Ikoro drum still echoes in oral tradition, not just as a warning of danger, but as a symbol of a people who stood together in the face of capture.

“Ihe onye metere na-eche ya” (Whatever a person does follows him). For the Igbo, resistance was not only an act of defiance but also a legacy that continues to follow their descendants, reminding them of the strength of unity.

References

- Basden, G. T. (1966). Among the Ibos of Nigeria. Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Oriji, J. N. (2007). Igboland slavery and the drums of war and heroism. Journal of African History, 48(1), 23–44.

- Talbot, P. A. (1921). The peoples of Southern Nigeria. Oxford University Press.