Ụwa bụ ndụ; ndụ bụ ụwa (The world is life, and life is the world).

The Forest as a Living Ancestry

In the time before tarred roads and concrete skylines, Igboland was a vast, breathing organism. The forest hummed with stories of spirits in trees, ancestors in rivers, and creatures that carried divine messages. To the Igbo, nature was not a background for human drama; it was the drama itself.

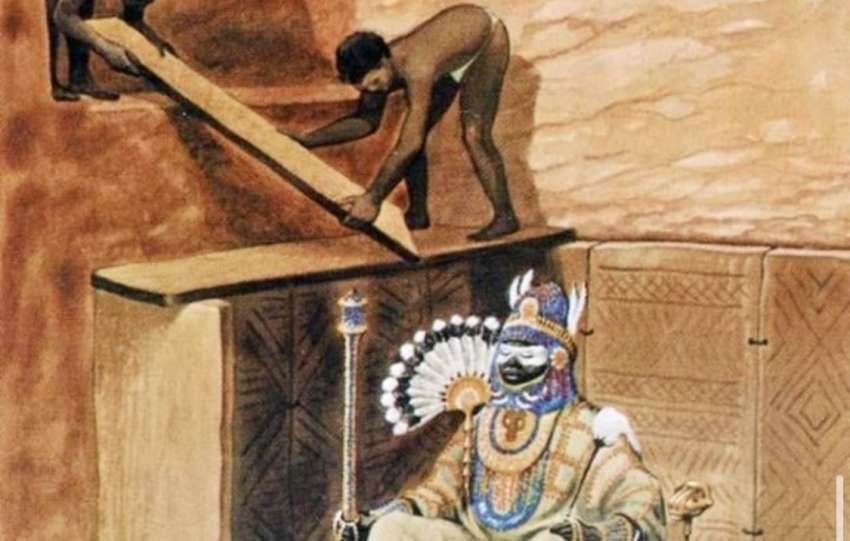

Totemism emerged as the covenant between humans and nature. Through it, certain animals, plants, or rivers were elevated from the ordinary to the sacred. The Eke Idemili python, the tortoise of Nsukka, and the crocodiles of Oguta Lake all became guardians of the people’s moral and ecological balance.

When an elder saw a python near his home, he would utter a quiet greeting, sprinkle palm wine, and allow it safe passage. To harm it was to invoke the wrath of the earth goddess, Ala. In these gestures, the Igbo preserved not just a creature but an entire ethic of coexistence.

Totems as Nature’s Silent Laws

Totemism operated as a spiritual constitution of ecology. Where the modern world writes environmental laws in books, the Igbo wrote theirs in the heart and conscience. A taboo was more binding than a decree because it carried spiritual consequence. For instance, in some parts of Anambra, fishing in certain streams during the dry season was forbidden, ensuring that aquatic life could reproduce. Communities that revered monkeys forbade hunting in their groves. These spiritual boundaries created invisible sanctuaries(natural reserves long before the idea of conservation entered textbooks). Even in farming, the Igbo observed rituals before cutting certain trees or clearing new land. A libation to Ala symbolized permission from the Earth herself. This ensured that human survival did not come at the expense of harmony.

Ọ bụ ihe mmadụ hụrụ n’anya ka ọ na-echekwa (One preserves what one loves). The Igbo preserved their forests because they loved them and not with sentiment, but with reverence born of belief.

The Circle of Life and Reciprocity

In the Igbo worldview, everything breathes within a circle of mutual dependence. Humans rely on the soil; the soil relies on the spirits; the spirits inhabit trees and animals. To break that chain was to cause nso ala( a pollution of moral and physical order).

Each totem animal represented a specific virtue.

- The tortoise symbolized wisdom and patience.

- The python represented purity and peace.

- The monkey embodied agility and vigilance.

When children learned these stories, they learned ecological ethics without calling it by name. A child who feared offending Ala would not destroy a nest, burn a bush, or pollute a stream. The divine eye of the land watched over all.

Totemism as Social Ecology

Totemism also structured the social fabric. Families were known by their totems (ụmụ eke, ụmụ enyi, ụmụ anụ, and others.) This spiritual identity created kinship not only among people but between people and the natural world. Festivals celebrated this harmony. The annual Iwa ji (New Yam Festival) was not merely a harvest feast but a thanksgiving to the forces that made growth possible the soil, the rain, and the unseen spirits guarding both. Songs and dances reminded communities that their survival depended on balance. In this way, every ritual reinforced ecological mindfulness. The earth was a partner, not a possession.

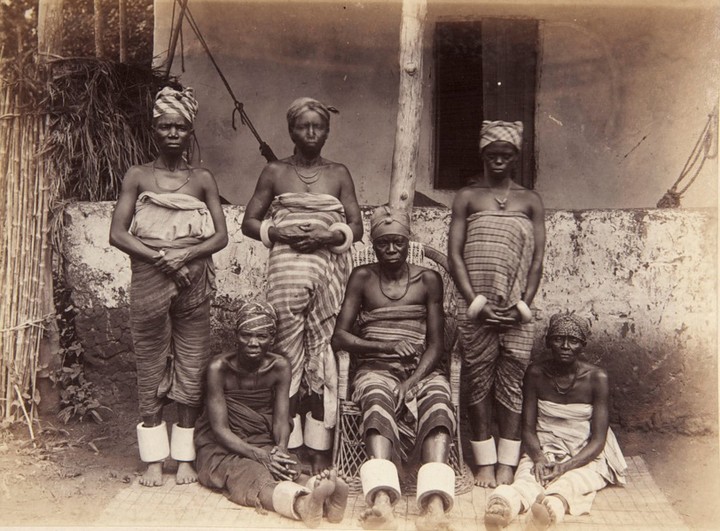

Modern Decline and Silent Forests

But with time came change. Christianity, colonialism, and modern education began to redefine sacredness. Pythons became pests, groves turned into farmlands, and taboos were dismissed as superstition. The spiritual boundaries that once protected nature weakened, and so did the forests. Today, only traces remain. Some elderly custodians still perform annual rites for the python in Idemili, or offer kola to rivers before crossing them. Yet the wisdom of totemism remains hidden, like a seed waiting for rain.

Mmiri anwụọla, azụ adịghịzi ama ebe e si eje mmiri (When the stream dries up, the fish no longer know where to swim). When humans forget their spiritual relationship with nature, both suffer.

Reclaiming the Ecological Spirit

To revive totemism’s wisdom does not mean returning to idol worship, but rediscovering what it taught, which is respect, moderation, and gratitude. These principles align with modern sustainability goals. Schools can teach Igbo folktales as environmental education. Communities can preserve ancestral groves as eco-parks. Religious leaders can reinterpret the message of Ala as one of moral responsibility for the planet. In combining tradition with science, the Igbo can once again become guardians of the wild, protectors of both spirit and soil.

Ala bụ ndụ; ọ bụghị mmadụ ka o ji ndụ (The Earth is life; it does not depend on humans to live). This proverb echoes humility, a reminder that the world existed before us and will outlast us unless we walk gently upon it.

References

- Ndubisi, E. J. O. (2021). Totemism in Igbo-African society and the preservation of the ecosystem. In I. A. Kanu (Ed.), African Indigenous Ecological Knowledge Systems (pp. 133–144). Augustinian Publications.

- Kanu, I. A. (2019). Ecology, spirituality and African traditional religion. Journal of African Environmental Ethics, 2(1), 45–58.

- Achebe, C. (1958). Things Fall Apart. London: Heinemann.

- Ogbalu, F. C. (1983). Igbo institutions and customs. Onitsha: University Publishers Company.