Nri culture is one of the most fascinating and significant subcultures in the Igbo cultural area. With unique title and religious systems, which have been adopted by much of Igbo land, Nri’s influence is undeniably profound and far-reaching. This level of impact makes it challenging to pinpoint what cultural practice specifically originates from Nri, and which comes from other Igbo communities. The widespread presence of certain Nri traits, such as the ichi facial marks and the Ozo title, corresponds with the reach of Nri influence in Igbo land.

Nri Kingdom’s title system is by far one of the major symbols of the kingdom. It is made up of an intricate hierarchy of titles such as the ichi (a facial scarification worn by men of distinction), Ozo (an esteemed title in Igbo land representing wealth, wisdom, and leadership), and other Nri titles. Surrounding these titles heavily is the Nri religious belief system that is grounded in sacred concepts such as Chukwu (the supreme God), Alusi (deities that represent various aspects of the natural and spiritual worlds), Mmuo (spirits), and Ifejioku (the god of yam cultivation, who is central to Igbo agriculture). Additionally, the ideology of abomination, which dictates what is considered to a be a taboo or sacrilegious, plays a key role in shaping Nri norms and religious rites.

Throughout the whole of Igbo land, titles and religious practices are found in various forms. Many believe that this is likely due to centuries of Nri influence. That being said, Nri culture as a whole, cannot be examined in isolation of the wider historical and cultural scope in which these practices evolved. This is because Nri culture is a central thread woven into the broader tapestry that holds Igbo cultures, norms and traditions.

The southeastern region of Nigeria is the home of Igbo people. It is a region known for its population density, trades economic and agricultural economy. As of 1963, the Igbo population was approximately 8.5 million, with 7.5 million residing in what was then known as the East Central State. Other Igbo communities also inhabited the northern part of Rivers State, as well as the eastern section of the former Mid-West State. Their high population coupled with their locations meant that there were over 1,000 Igbo people per square mile in some areas. This reflects level of economic and social activity of the region.

Economically, Igbo people have always capitalised on the resources available in the West African equatorial forest, particularly the palm fruit. Palm produce was a major commercial crop that acted as the driving economical force in the region. Other crops that contributed to economic success and sustenance were yams, cocoyams, maize and cassava. In the craftsmanship sector, bronze casting, ironwork, pottery and woodworking exhibited the artistry of Igbo people. These crafts date centuries back, and were evidenced through the archeological discoveries of renowned works like the Igbo-Ukwu, which was examined in the ninth century AD.

Most of the craftsmanship continues to flourish even today, however, the bronze casting has diminished greatly. Nevertheless, these trades remain significant markers of the Igbo culture.

Credit: Professor Thurstan Shaw

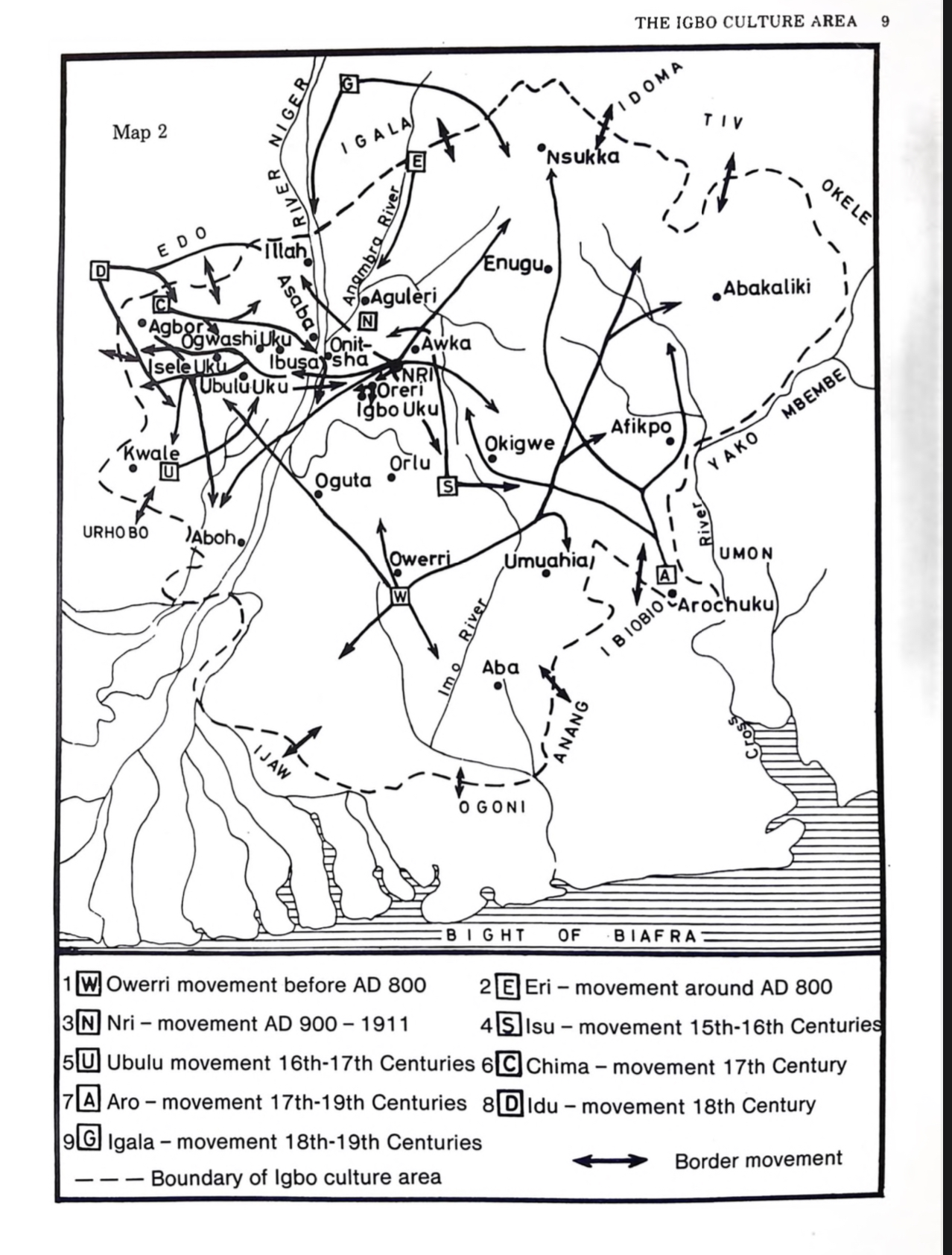

What is considered to be the Igbo culture area is in fact an imaginary line encircling settlements such as Agbor, Kwale, Arochukwu and Enugu areas. Characterising this area are settlement patterns that range from dispersed to compact. Within this region, the Igbo live in patrilineal units known as Umunna. These patrilineages are ranked based on size and importance, from minimal to maximal. Federations of these patrilineages form villages. Multiple villages then unite to form towns (obodo), and these towns each hold their own political autonomy, especially regarding territorial and religious matters.

Just like other Igbo groups, the Nri have migrated far and wide within the south eastern region of Nigeria. This shaped their territorial growth and political structures. Examples of such exodus include the Nri movement that most likely occurred between AD 900 and 1911. The Eri movement around AD 900 is another example as well as the Isu movement during the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. These resettlements, although distinct, contributed to the wider cultural and political landscape of the Igbo people.

According to the Nri traditional way of thinking, leadership is intimately tied to the idea of the head. The isi (head) is considered the seat of both wisdom (amamife) and life (ndu). The symbolic nature of the head is pervasive in Nri society. During rituals, for example, the skull of a sacrificial animal can serve as a representation of the animal itself in religious ceremonies. This reverence for the head also exists within the political sphere, where leaders are referred to as one (the person at the head).

When it comes to leadership, Nri society is made up of various levels of authority. The king of Nri (Eze Nri), is not simply a chief or local leader, but the sovereign ruler of a kingdom. Spiritually, politically and historically, Eze Nri holds immense power. The sovereignty with which Eze Nri operates is why they often refused to accept titles imposed by foreign powers. An example of this would be Eze Nri Obalike, who famously rejected the British colonial government’s attempt to appoint him as a warrant chief in 1910. Another example follows Eze Nri Nrijiofo II, who refused to participate in the competition for a second-class chieftainship in 1960, preferring to maintain the traditional authority of the Nri kingship. This strong resistance to foreign titles reflects the view of leadership held in Nri: the Eze Nri is a force whose authority transcends mundane political structures. Societally, knowledge and wealth are valued in Nri as essential for leadership, even though they aren’t interchangeable. True leadership requires a combination of knowledge (particularly in Nri tradition and religion), and wealth. Wealth is measured by the amount of one’s material assets- livestock, yam barn, property, and family size. However, possessing these qualities alone doesn’t constitute a leader. There is a title-making process, especially through the prestigious Ozo title, that is necessary to legitimise one’s leadership within the community.

In Nri, leadership operates on multiple levels. From age-grade systems to lineage councils and state-wide councils of elders. These layers enhance a decentralised and hierarchical form of leadership. By so doing, different groups can exercise their authority in their respective domains. Due to the significance of lineages, the Nri political organisation is deeply embedded in kinship ties. In the early parts of Nri’s history, groups lived independently of one another, with each group maintaining its own religious and political systems. But over time, these groups banded together under the one.

Sovereign leadership of the Eze Nri. This way, the previously separate groups became a cohesive political identity, whilst still preserving their territorial identities. Territoriality was therefore crucial in the shaping of political dynamics in Nri. Initially, the town of Nri was originally divided into segments. These segments were UmuDiana, Agukwu, and Diodo, and they each had their leadership structures and landholdings. Over time, the three segments under Eze Nri’s authority retained a degree of autonomy in their internal affairs.

Despite Nri’s kinship-based political structures, several political groups were non-lineage-based. These groups operated as corporate entities that were bound by religious or political obligations as opposed to family ties. For instance, the Ndi Nze Nri were made up of Ozo title holders. These titled men represented a politically elite group whose authority stemmed from both religious and societal norms. They held significant sway in decision-making processes, and because of this, they often met in councils to advise the Eze Nri on state matters.

The mark the Nri people have left on the broader Igbo landscape is undeniable. Their title-taking systems, religious beliefs, and leadership structures have not only shaped their society but have also influenced neighbouring Igbo communities. As one of the oldest and most complex political entities in Igboland, Nri remains a testament to the rich and multifaceted history of the Igbo people.

References:

- The Dawn of Igbo Civilization in the Igbo Culture Area’, in Odinani, Journal of Odinani Museum, Nri. Vol. 1, No. 1, March 1972.

- TERRAY, E. 1972. Marxism and ‘Primitive’ Societies New York and London.

- SMITH, M.G. 1956. ‘On Segmentary Lineage Systems’. Journal Of Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. 86, No. 2, London.

- Onwuejeogwu, M. A. (1981). An igbo civilization: Nri kingdom & hegemony. Ethnographica ; Ethiope.