The story of a people is not written in dust, it is etched in memory, song, and story. For the Igbo, whose history was long spoken before it was written, the historians became the ndi na-ede akụkọ ndụ ( the recorders of life).

Before the ink of independence dried, before Nigeria found its voice, a few sons and daughters of Ala Igbo picked up their pens to document the wisdom, struggles, and triumphs of their people. They became the guardians of memory, ensuring that the past would never be forgotten.

As the Igbo say, “Onye na-amaghị ebe mmiri bidoro maba ya, agaghị ama ebe ọ ga-ama ya.” (He who does not know where the rain began to beat him cannot know where he dried his body). So, they wrote to remind us where the rain began.

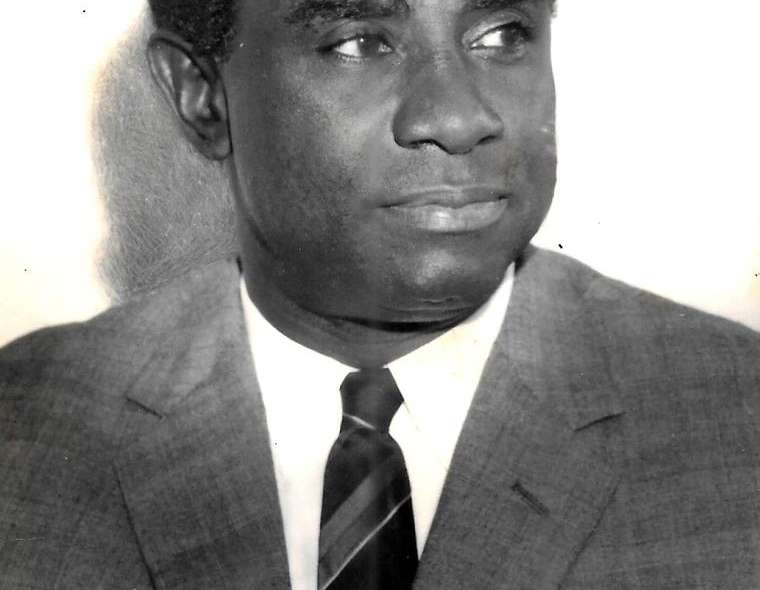

Kenneth Onwuka Dike: The Father of African History

Born in Awka in 1917, Kenneth Onwuka Dike changed the way Africa told her story. Before him, much of African history was told through colonial eyes. But Dike, with the grace of an elder storyteller, reclaimed that narrative. His groundbreaking book, Trade and Politics in the Niger Delta, shattered the myth of a “people without history.”

Dike founded the Department of History at the University of Ibadan and became the first Nigerian Vice-Chancellor. He trained generations of historians, urging them to look inward, to oral traditions, folklore, and ancestral memory.

He once said that “Africa must tell her own story, for only then shall the world know her truth.” In that spirit, Dike became the ọkpụkpọ nke akụkọ (the herald of African historiography).

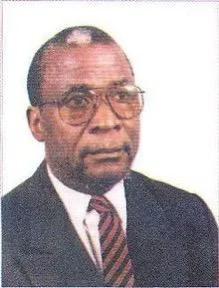

Adiele Afigbo: The Chronicler of Igbo Civilisation

If Dike built the foundation, Adiele Eberechukwu Afigbo (1937–2009) raised the walls. Afigbo’s scholarship was a bridge between the ancestors and the modern world. From his studies on the Warrant Chiefs to his essays on Igbo political systems, Afigbo gave voice to the subtle rhythms of precolonial life.

He saw the Igbo not as fragmented villages, but as a civilisation bound by culture, commerce, and kinship. Through his words, the world understood that the Igbo nation had a system, one not built on kings but on ọha na eze (the collective will of the people). As elders would say, “A sị na ọnụ ndị mmadụ ka e ji ama mmadụ” (A person is known through the voice of their people). Through Afigbo, the Igbo spoke; loud, proud, and scholarly.

Source: Biographical legacy & research foundations

Don C. Ohadike: The Voice of Resistance

Born in 1941, Don Ohadike told stories of rebellion, courage, and collective spirit. His book, The Ekumeku Movement, remains a testament to the Igbo resistance against British imperialism. Ohadike’s writing pulsed with the fire of liberation, the spirit of ogu na okwu (truth and struggle). His research restored the dignity of those who fought not with guns alone, but with belief and unity. In his hands, history became a drumbeat of freedom. “Mgbe mmadụ jụọ ihe mere, akụkọ adịghị efu” (When people ask what happened, the story does not die).

The Modern Torchbearers: Nwando Achebe, Emeka Keazor, and Apollos Nwauwa

Professor Nwando Achebe, daughter of the literary giant Chinua Achebe, blends gender, culture, and oral history. Her works highlight women as central figures; priestesses, traders, queens, and healers, often forgotten in patriarchal narratives. Her scholarship reminds us that “anyị bụ otu” (we are one), bound by shared humanity.

Emeka Ed Keazor, historian and lawyer, uses multimedia storytelling to bring the past alive through documentaries, archives, and films. His work reconnects young Igbo minds with their roots in a digital age.

Apollos Okwuchi Nwauwa, a professor in the United States, continues the academic lineage of Dike and Afigbo, studying Nigerian education, culture, and politics from a transnational lens.

Together, they prove that the akụkụ akụkọ (pages of history) are still being written.

Beyond the Igbo: The Friends of Igbo History

Not all who told the Igbo story were Igbo. British scholar Margery Perham and Nigerian historian Tekena Tamuno studied Igbo society with depth and respect, helping global audiences understand the heart of Eastern Nigeria.

Perham’s early works, though written in a colonial era, captured the vibrancy of Igbo social structures. Tamuno, a Niger Delta historian, emphasised unity in diversity, showing how Nigeria’s many peoples share common destinies. It was, as Zik of Africa would say, “a fellowship of the pen”.

Legacy: Writing as Liberation

From Awka to Nsukka, from Ibadan to Michigan, the spirit of Igbo historiography thrives. These historians did not merely record events; they redefined existence. They taught us that history is not a collection of dates, but a living ọfọ (a sacred staff of truth). They proved that to remember is to resist erasure, and they left us with a message as timeless as the proverbs they loved: “Akụkọ ọma anaghị agba oge ” (A good story never grows old ). Through their ink, the Igbo story endures: a story of resilience, wisdom, and pride.

References:

- Achebe, N. (2011). The Female King of Colonial Nigeria: Ahebi Ugbabe. Indiana University Press.

- Afigbo, A. E. (1981). Ropes of Sand: Studies in Igbo History and Culture. Oxford University Press.

- Dike, K. O. (1956). Trade and Politics in the Niger Delta, 1830–1885. Oxford University Press.

- Igbo People Biography. (2025). Igbo Historians.

- Ohadike, D. C. (1991). The Ekumeku Movement: Western Igbo Resistance to the British Conquest of Nigeria, 1883–1914. Ohio University Press.

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2025). Category: Igbo Historians.