“Okwu bụ ndụ.” (Words are life). The old proverb could well summarise Emenyonu’s life’s work. To him, literature was not simply art; it was history, language, and identity woven together like the intricate threads of akwete cloth.

From Umuahia to the World

Born in Umuahia, Abia State, in the heart of Igboland, Ernest Nneji Emenyonu grew up surrounded by tales of heroes, tricksters, and ancestral wisdom passed from mouth to mouth under the moonlight. The evening fireside stories (akụkọ ifo) of his childhood would one day fuel his passion to prove that these oral traditions were the real roots of Igbo literature.

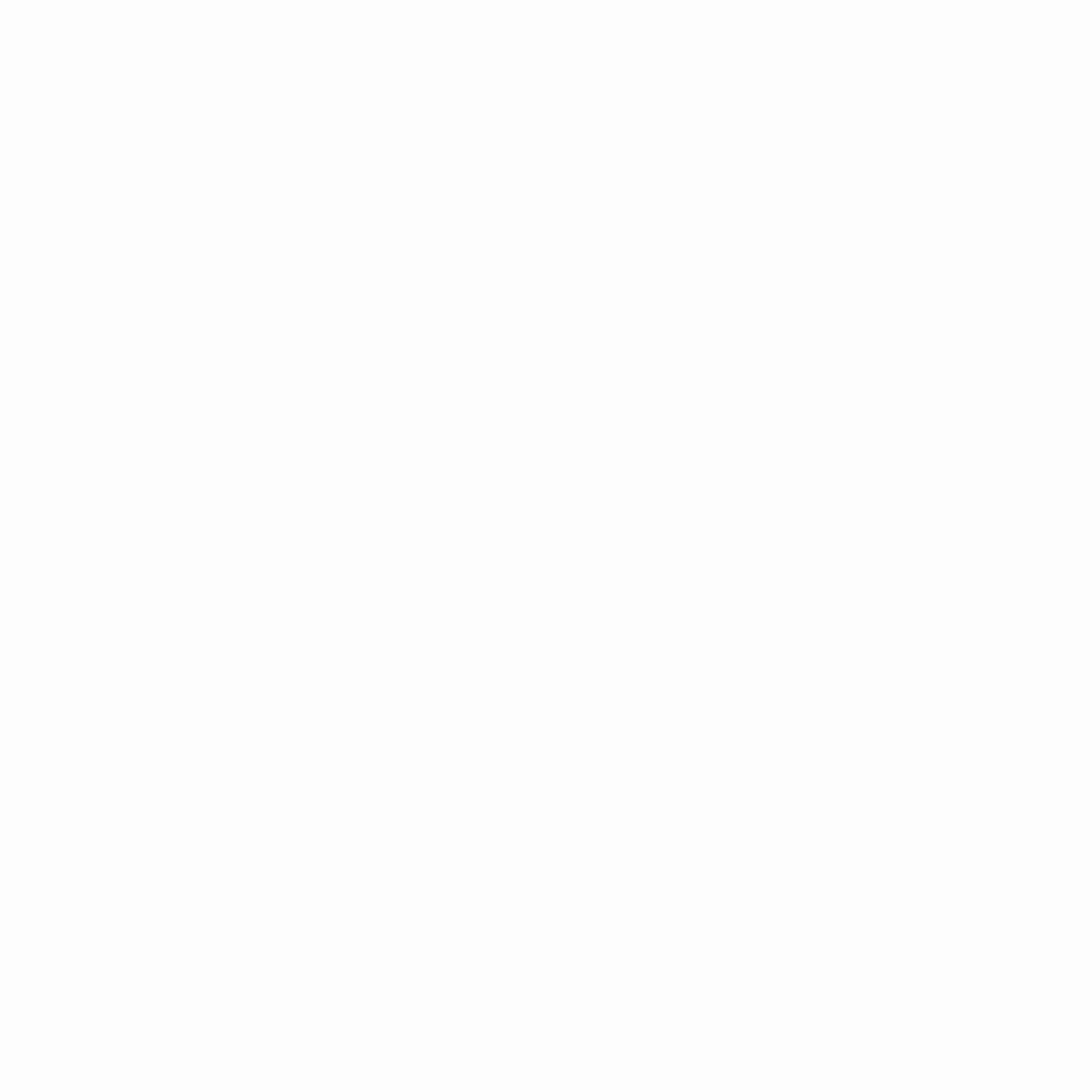

After completing his early education in Nigeria, Emenyonu pursued higher studies abroad, earning advanced degrees in literature and education. Yet, wherever he went, his heart remained tethered to the Igbo word. In lecture halls in Michigan or Nigeria, his tone carried the rhythm of Ọja flute; calm, thoughtful, and deeply rooted.

He believed that “no people can truly be free if they forget how to speak in their own tongue.” As the Igbo say: “Asụsụ bụ ihe mkpuchi nke mmadụ.” (Language is the garment of a person).

Rediscovering 1857: The Birth of the Igbo Novel

Before Emenyonu’s research, many scholars thought Igbo literature began with the post-independence generation of writers: Achebe, Nwapa, and Okigbo. But in his groundbreaking work, The Literary History of the Igbo Novel: African Literature in African Languages (2020), Emenyonu traced Igbo literary expression back to 1857, when the earliest translations of Christian texts and folktales were documented in Igbo.

Through painstaking archival research, he revealed how those early writings formed the seeds of modern Igbo literature; how storytelling evolved from oral performance to written art without losing its spiritual pulse. His study illuminated the continuity between the fireside tale and the printed page.

Champion of Literature in African Languages

At a time when English-dominated academic writing, Emenyonu dared to insist that African literature written in African languages was not a side note; it was the main text. His advocacy inspired generations of writers and scholars to publish in Igbo, Yoruba, Swahili, and Shona.

As a long-time editor of African Literature Today, Emenyonu created a platform for African voices to critique, celebrate, and document their own literary traditions. His vision was Pan-African but always rooted in Ala Igbo, the ancestral soil that nurtured his worldview. He once wrote, “To deny a people the dignity of their language is to deny them their history.” That conviction made him a cultural bridge, connecting African intellectuals from Accra to Nairobi, from Nsukka to Michigan.

The Igbo Spirit of Memory

What made Emenyonu unique was not just scholarship; it was his spirituality. He viewed literature as a repository of memory, a sacred space where ancestors and the living converse. He often invoked the proverb: “Onye na-amaghị ebe mmiri bidoro mụọ ya agaghị ama ebe o kwụsịrị ịkpọ ya.” (He who does not know where the rain began to beat him will not know where it dried his body).

Through his studies, Emenyonu sought to remind the Igbo where the rain began, in their language, in their myths, in their written and unwritten texts. His work reframed literature not as colonial inheritance but as ancestral continuity.

Legacy and Reflection

Today, when scholars discuss the history of the Igbo novel, they begin not in 1958 with Achebe’s Things Fall Apart but in 1857, thanks to Emenyonu’s meticulous reconstruction. His research demonstrated that the Igbo have always been storytellers, that colonial languages may have documented the form, but the Igbo soul authored the content.

Beyond academia, his legacy lives in how he inspired young writers to look inward. He often told his students, “You are not discovering African literature, you are remembering it”. And perhaps, in the quiet after his lectures, one could hear the echo of ancestral drums reminding us that stories are bridges, carrying the voices of the past into the hearts of the future. “Ihe onye dere, ọ ga-adị ndụ.” (What one writes will live forever). Ernest Emenyonu’s words live and through them, Igbo literature breathes.

References:

- Emenyonu, E. N. (2020). The literary history of the Igbo novel: African literature in African languages. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

- Nnadi, G. (2022, February 18). The Igbos & Yorubas of Sierra Leone. Retrieved from georgennad.wordpress.com

- Ogbu, C. (2020). Evolution of the Igbo novel. Academia.edu.

- Open Access Publishing. (2020). African Literature in African Languages – External Content PDF. OAPEN Library.