Albert Chinụalụmọgụ Achebe was born on November 16, 1930, in Ogidi, Anambra State, a town alive with tradition and folklore. His name, Chinụalụmọgụ, means “May God fight on my behalf”, a prophetic prayer that foreshadowed the literary battles he would later wage for African dignity.

Achebe grew up at the crossroads of two worlds. His father, Isaiah Okafọ Achebe, was a Christian catechist; his mother, Janet Anaenechi, carried deep knowledge of Igbo oral traditions. In this home, the Bible met ụzọ ndi Igbo (the Igbo way), and young Achebe learned early that stories shape how a people see themselves.

It was in those early years that he heard folktales under the moonlight, tales of Tortoise the trickster, Sky God, and Eke, the serpent of wisdom. These became the seeds of his lifelong conviction that “until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

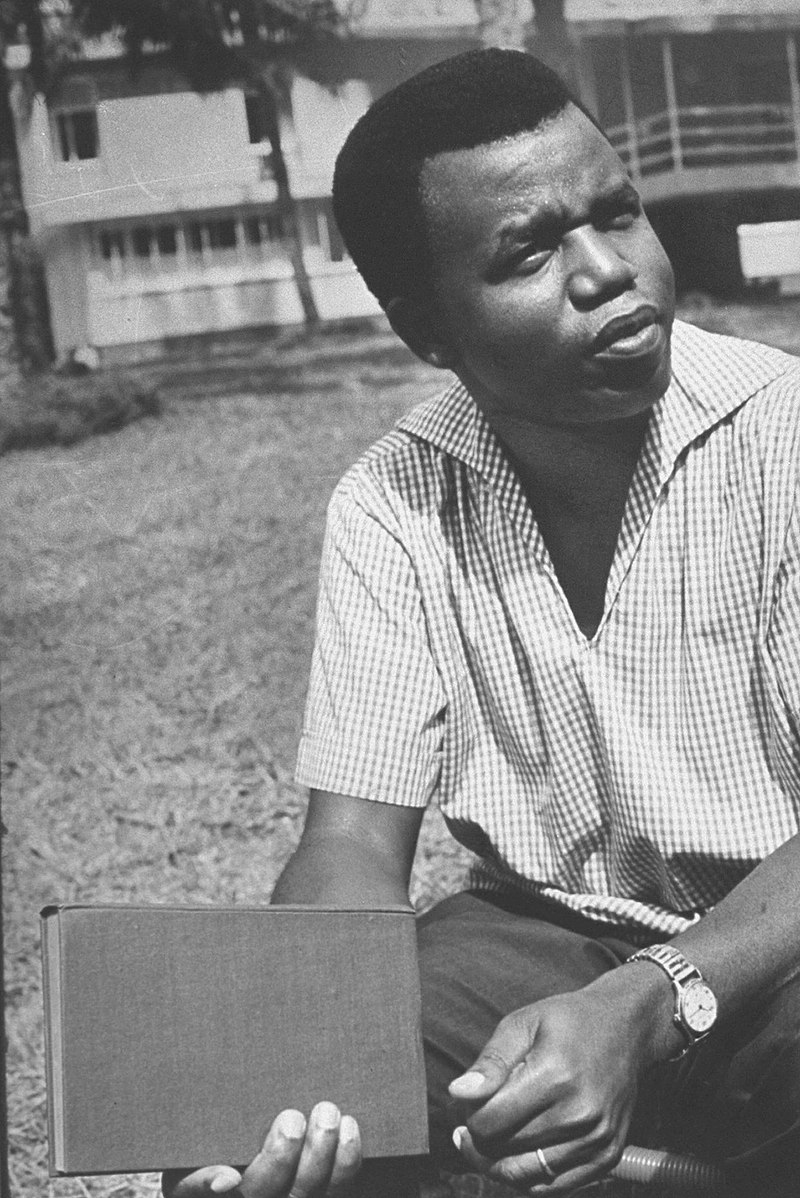

Education and the Making of a Writer

Achebe’s academic brilliance carried him to Government College, Umuahia, and later to University College, Ibadan, where he studied English, history, and theology. It was there that he first encountered the works of Shakespeare, Joyce, and Conrad. Yet, as he read European depictions of Africa, he felt a stirring anger. In books like Heart of Darkness, he saw his continent portrayed as dark and primitive. Achebe once wrote that those stories “robbed Africa of its humanity.” It was in this moment that the young man from Ogidi decided to tell his own version of the African story, one that carried truth, dignity, and mmụọ Igbo (the Igbo spirit).

As an editor at the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation, Achebe began to refine his voice. The stories of his people, their laughter, proverbs, and tragedies, became the ink with which he would write himself into history.

Things Fall Apart: A Voice for Africa

In 1958, at only twenty-eight years old, Achebe published “Things Fall Apart.” It was more than a novel; it was a reclamation of identity. Through the tragic figure of Okonkwo, Achebe told the story of precolonial Igbo society and its disruption by British imperialism.

The title, taken from W. B. Yeats’ poem, symbolised the shattering of worlds, but Achebe’s tone was not despair; it was clarity. He wrote with the rhythm of Igbo speech, the wisdom of proverbs, and the empathy of a storyteller who loved his people.

He once said, “Proverbs are the palm oil with which words are eaten.” In Things Fall Apart, proverbs flow like the River Niger; they teach, warn, and heal. From “When the moon is shining, the cripple becomes hungry for a walk” to “A man who brings home ant-infested faggots should not complain when visited by lizards,” the novel became a vessel of Igbo philosophy. The world listened. Things Fall Apart was translated into more than 60 languages and sold over 20 million copies, making Achebe the most widely read African author in history.

The Chronicler of a Changing Nation

Achebe’s subsequent works, No Longer at Ease, Arrow of God, A Man of the People, and Anthills of the Savannah, continued to explore the collision between tradition and modernity, morality and power, hope and disillusionment. In Arrow of God, he presented Ezeulu, a priest torn between divine duty and colonial intrusion. The story reflected Achebe’s own lifelong tension between faith and culture, progress and preservation.

During the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), Achebe sided with Biafra, serving as an ambassador and cultural voice for his people. The war left deep scars, yet it also reaffirmed his belief in the power of the written word to bear witness. He wrote, “The writer cannot be excused from the task of re-education and regeneration that must be done.” Achebe’s later years were marked by essays and speeches that combined moral clarity with scholarly precision. He became a literary conscience, reminding Africa and the world that to lose one’s story is to lose one’s soul.

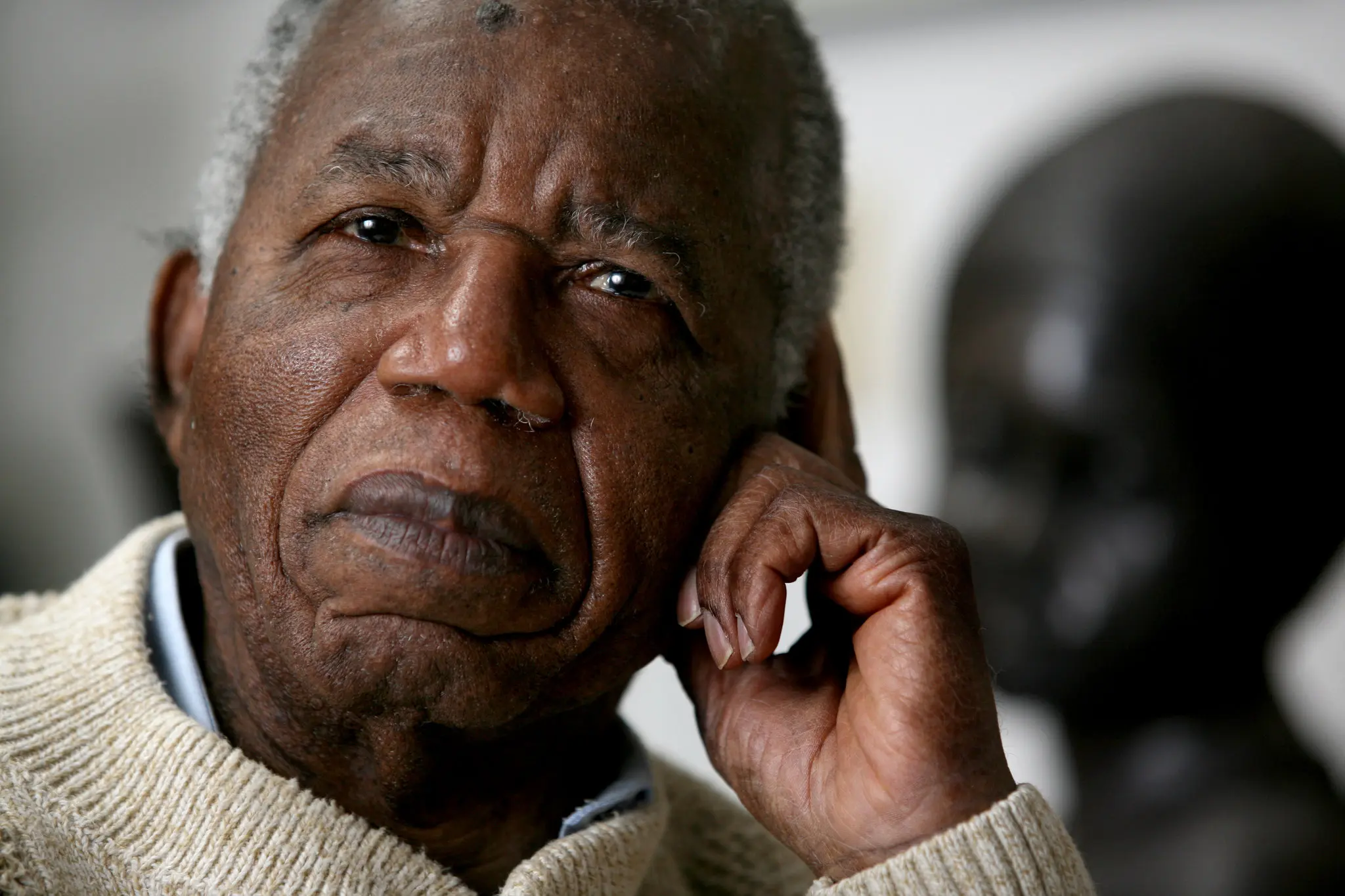

Global Legacy and Cultural Continuity

In 2007, Achebe received the Man Booker International Prize, and in 2010, Nigeria honoured him with the Commander of the Federal Republic (CFR) title. His writings influenced generations, from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, and inspired African literature to stand proudly in its own language, tone, and rhythm.

Achebe lived in the United States for many years, teaching at Brown University, but his heart remained in Ogidi. Even after a car accident in 1990 that confined him to a wheelchair, he continued to write with unbroken vigour. He passed away on March 21, 2013, in Boston, yet his spirit lives on in the lines of his novels and the hearts of readers. As Igbo elders say, “Mmadu adighi anwu n’ala mmụọ” (The person does not die in the land of spirits). Achebe’s presence, like the ancient storytellers, still echoes wherever truth and wisdom are spoken.

Proverbs and the Achebean Spirit

Achebe’s works remind us that literature is not merely art; it is memory and moral compass. He taught that a nation that forgets its storytellers forgets itself. His pen bridged worlds, carrying the ụzọ Igbo (Igbo way) into global consciousness.

As an Igbo proverb says, “Nwoke adịghị egbu okwu, ọ bụ okwu ka e ji egbu nwoke” (A man does not kill words, but words can kill a man). Achebe understood this power and wielded it to dismantle stereotypes and build bridges of understanding.

References:

- Biography.IgboPeople.org. (n.d.). Chinua Achebe.

- Britannica. (2024). Chinua Achebe.

- HursandRyder. (n.d.). Biography: Chinua Achebe.

- Wikipedia. (2024). Chinua Achebe.

- Writers Inspire. (n.d.). Chinua Achebe biography.